In Memoriam

Justin Bisson (1985 – 2020)

Fear no more the heat o’ the sun,

Nor the furious winter’s rages;

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages:

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

Fear no more the frown o’ the great;

Thou art past the tyrant’s stroke;

Care no more to clothe and eat;

To thee the reed is as the oak:

The scepter, learning, physic, must

All follow this, and come to dust.

Fear no more the lightning flash,

Nor the all-dreaded thunder stone;

Fear not slander, censure rash;

Thou hast finished joy and moan:

All lovers young, all lovers must

Consign to thee, and come to dust.

No exorciser harm thee!

Nor no witchcraft charm thee!

Ghost unlaid forbear thee!

Nothing ill come near thee!

Quiet consummation have;

And renownèd be thy grave!

William Shakespeare, Cymbelline

CONTENTS

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

Jekyll Island Golf Club Origins: A Mysterious Myth

Golf Club Versus Golf Course

First Golf

First Golfers

A Golf Convenience

Locating the Golf Ground

Island Landscape North of the Clubhouse

Open Ground

Fields

Quail Meadows

The Gamekeeper’s House

Rating the Golf Convenience

Jekyll and Hyde

Golf-Mad Jekyll Islanders

George Jay Gould

J. Pierpont Morgan, Sr

William Bayard Cutting, Sr

Arthur Brigham Claflin

Southern Resort Rivalry

“The Thing” to Do

A Golf “Convenience” Designer?

Sniping

The Hunting Imperium of Dean Hoffman

The Best Quail Land

The Sniping King

Gunners versus Golfers

Compliments of Charles Lanier

Not Hyde-Bound to Hunting Grounds

Wherefore a Dunn Deal?

The Unknown Golf Courses of Willie Dunn, Jr

Dunn’s Twice-Told Tale

The One Tale

The Other Tale

Untold Tales

Two Visits

Scouting Jekyll Island Golf Sites

Showing the Club

The Timing of a “Temporary Arrangement”

Harder Than Expected

The 1897 Willie Dunn Course

About “Bogey”

About Six Inches of Scorecard

“Between the Morris Home and the Bridge”

Charles Stewart Maurice

Hi-Ho the Dairy! Oh ... ?!

How long did this “temporary” golf course last?

Rating Dunn’s 1897 Riverside Course

The Honest Son of Abe

John D. Rockefeller

Two Towers and a Windmill

Flagging a Location

Present Arms

Caddie Identification

Underwood and Underwood

Jekyll Caddies

William Inglis and William Hemingway

“Oily John” and the Two Willies

Rockefeller Lets President-Elect Taft Play Through

Sartorial Signals

Shadowy Information

Tee Box Northward

Tee Boxes Southward

Fairways

Sand Greens Generally

Sand Versus Grass in the South

“Riverside” Sand Greens Particularly

The Mystery of the White Caddie

That’s Rough

Aim Line: First House or Second House?

Dunn’s “Savanna” Course

Dunn as Designer

Not Doing Anything Not Necessary Now

Construction

The Fickle Finger of Fate

Bermuda Grass

Horace Rawlins

Dunn’s “Savanna” Undone

The Experience of the Hurricane on the Riverside

Dunn’s Savanna Course Legacy

The Travis Consultation

Whence Travis?

Travis versus Dunn

Caught Between a Penal Rock-Wall and a Strategically Hard Place

Travis Modifications?

A New Course

Before Donald Ross, Jock Hutchinson

The Ross Design

The Eighteen-Hole Course

The Nine-Hole Course

Construction

Earliest Photographs of the Ross Course

Pinehurst and Jekyll Island Greens

Photographs of the Layout

Ross and Dunn Ditches

“Dunn” and “Ross” Played the Same Day?

Ross Course Reviews

Between a Ross and a Travis Place

Karl Keffer

Keffer and Travis

Designing Ambitions

First Two Dunes Holes

Niblick and Beers

The Par Three by the Sea

Keffer and Francis Ouimet

Keffer, Travis, and Ross

Golfing to War

The War Pro Shop at Royal Ottawa

World War I and Golf Course Design

Back in the Game

The Jekyll Island Pro Shop

Earl Hill

More Dunes Holes

Three More Dunes Holes

Three More Not-So-Dunes Holes

A Grand Opening

Balls to Jekyll Island

Algernon P. Grass, Not

Grass Greens

Reviews

Another New Course? What Gives?

The Changa Crisis of 1925

Plus ça changa

The Scorecard of the Oceanside Course (a.k.a. Great Dunes)

The Lost Nine

A Review of the 2/3 Travis, 1/3 Keffer Oceanside Course

Post-War Keffer and His Part of the Dunes Course

Foreword

Not long ago, I discovered that the course record at the club where I was a member, the Napanee Golf and Country Club (founded in 1897), was held before World War I by a young Canadian professional golfer from Toronto by the name of Karl Keffer, who would win the Canadian Open in 1909 and 1914.

I then discovered that while Keffer was the head pro at the Royal Ottawa Golf Club (where he served from 1911 to 1942) he laid out two of the other golf courses that I play most frequently in the Ottawa Valley. Almost 100 years later, the holes that he designed remain a great pleasure to play.

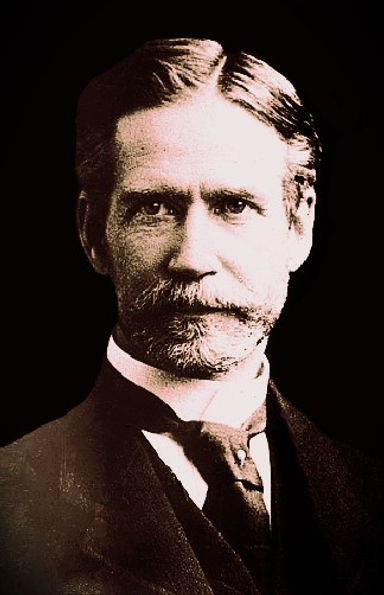

Figure 1 Karl Keffer, circa 1909.

Deciding to look further into the history of this golfer and course designer, I immediately discovered that Keffer had a winter career in Georgia parallel to his summer career at Royal Ottawa. From 1910 to 1942, he enjoyed a thirty-three-year residence as head pro for the millionaires of the Jekyll Island Club located on Jekyll Island, Georgia.

What else I eventually discovered surprised me and will surprise others familiar with accounts of the development of golf on Jekyll Island.

It turns out that Karl Keffer designed a nine-hole golf course for the Jekyll Island Club, whose multi-millionaire members were said to possess one-sixth of the world’s wealth at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Very few people know about the Keffer course today. It never had a name. Yet, as we shall see, it received a stellar review from the editor of Golf Illustrated in 1925.

Although it was combined with a nine-hole circuit by Donald J. Ross to form an eighteen-hole championship course, the Keffer course built in the Jekyll Island dunes was described hole-by-hole by the magazine’s well-respected, links-loving, golf-savvy editor – he said one hole was a “great hole” and that the next hole was “the best he knew” of in the

world – and yet he said nary a word about the other nine holes designed by one of America’s greatest golf course architects.

I call this glorious unknown golf course “Keffer Dunes.”

This book tells the story of the early golf courses designed on Jekyll Island between the 1890s and the 1920s – a story that culminates in an account of “Keffer Dunes.”

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to Janet M. Childs, who provided instrumental assistance in the production of this book through her formatting skills, her proofreading efforts, and her perspicacious criticism.

I thank U.S.G.A. Historian Maggie Lagle for generously sharing with me the Jekyll Island scorecards possessed by the U.S.G.A. and the U.S.G.A. file on the history of the Donald J. Ross course on Jekyll Island by James S. Brunner: “Jekyll Island Golf History – The 1910 Donald Ross Course,” June 1998, U.S.G.A. Archives.

Also quite helpful has been feedback from Andre Marroquin, Curator, Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum, who read the manuscript.

I am especially grateful to Kyle Keffer and members of the Keffer family for information about Karl Keffer and Evelyn Alice Keffer (née Freeman).

Preface

The story of golf course design on Jekyll Island before World War II is rich with the names of renowned architects: Willie Dunn, Jr, Donald J. Ross, Walter J. Travis.

Furthermore, equally celebrated golf course architects such as Charles Blair Macdonald and Albert Warren Tillinghast came to Jekyll Island to play its earliest golf courses.

And after World War II, when the state of Georgia took over Jekyll Island, no less an authority than Robert Trent Jones, Sr, was brought in to assess the condition and viability of its golf facilities, which had been totally neglected since the evacuation of the island in 1942 as a safety precaution during World War II.

But despite the golf world’s great interest in such figures, the story of early golf course design on Jekyll Island – as told so far – is in important respects incomplete, uncertain, and confused.

How many courses were built before World War II? Who designed them? When was each course built?

How long did the various courses last? When were they remodelled and who remodelled them?

Did these courses have nine holes or eighteen holes?

In the nineteenth century, there was a plan for a twenty-seven-hole two-course development: what became of it?

In the early 1920s, there was a fourteen-hole course: what is the story behind that?

Initially, all putting “greens” were made of sand. Then they were made of “oiled sand.” When were they converted to grass?

The answers to these questions are not easy to find, but such answers as can be found are always interesting, and often fascinating.

Research reveals that the story of golf course design on Jekyll Island largely leaves out the most enduring contribution – that of its golf professional from 1910 to 1942: Karl Keffer. Perhaps this omission is understandable given how well-known and historically significant the other golf course architects are, but Keffer was a designer of golf courses, too. He designed many golf courses in Canada – several nine-hole layouts in Ontario and Quebec after World War I and an eighteen-hole layout in 1929 for the Glenlea Golf and Country Club (today called the Champlain Golf Course). But before his Canadian ventures in golf course architecture, he built a nine-hole golf course on Jekyll Island between 1913 and 1923 that literally linked the 1909 Donald Ross course to the Great Dunes course of Walter J. Travis, begun in the fall of 1926. Travis went on to incorporate most of the Keffer course into his Great Dunes course.

It seems to have been the popularity of the nine-hole Keffer course located in the Jekyll Island dunes along the Atlantic coast that led to the commissioning of Travis to develop a full eighteen-hole dunes course in this area. The Keffer dunes course had already supplanted the nine-hole Ross course as the favorite nine-hole circuit on Jekyll Island (especially in the opinion of the younger members). Travis seems to have been made aware that Club members were very happy with their existing Keffer dunes holes; he was to add to them.

Travis kept five of Keffer’s holes exactly as they were, divided one of Keffer’s holes in half to create two holes, and then added eleven brand new holes to create a new eighteen-hole course that Club members called the “Oceanside Course,” although it is now known by the name Travis himself used: Great Dunes. Ironically, however, although only nine holes of Great Dunes survive today, and Keffer designed by far the majority of them, the prominence of Travis as a golf course architect has obscured Keffer’s connection with what became a very famous golf course. In 1947, there was no mention of Keffer in the Philadelphia Inquirer’s reference to the golf course about to be acquired by the state of Georgia: “An 18-hole golf course, laid out by Walter J. Travis, one-time United States amateur champion, is one of the finest dunes courses in North America” (Everybody’s Weekly, Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 July 1947, p. 10).

As we shall see, however, the fact remains that Karl Keffer was the designer of the oldest golf holes still in play on Jekyll Island today.

Introduction

Figure 2 Willie Dunn, Jr, 1894.

Willie Dunn, Jr, is sometimes honored as the first U.S. Open champion, having won the open championship held in 1894 several months before the United States Golf Association was formed and undertook to conduct the official U.S. Open ever afterward, but he is also a key figure in the development of golf on Jekyll Island.

Soon to become a ubiquitous architect who would design many dozens of golf courses throughout the American Northeast and Midwest during the 1890s, Dunn actually claimed that he had turned the focus of the late nineteenth-century sporting clubs of America’s wealthiest men (like the millionaires’ club at Jekyll Island) from hunting and fishing to golf several years before he even set foot in North America.

By Dunn’s telling of the tale, he did so with a golf shot heard round the rich man’s world:

It was in France that three American sportsmen, W.K. Vanderbilt, Edward S. Meade, and Duncan Cryder, first became interested in the game and got the idea of building a course in the States. In 1889 I was engaged in laying out an 18-hole course at Biarritz, France. Biarritz at that time was a small village, and there were few tourists from America. I had nearly completed the Biarritz links when I met Vanderbilt, Meade and Cryder. They showed real interest in the game from the beginning; I remember the first demonstration I gave them. We chose the famous Chasm hole – about 225 yards and featuring a deep canyon which has to be cleared with the tee shot; I teed up several balls and laid them all on the green, close to the flag. Vanderbilt turned to his friends and said, “Gentlemen, this beats rifle shooting for distance and accuracy.” Soon afterwards these men asked me to come to America and build a golf course there. (“Early Courses of the United States,” Golf Illustrated, vol 41 no 6 [September 1934], p. 24)

By Dunn’s telling of the tale, he did so with a golf shot heard round the rich man’s world:

It was in France that three American sportsmen, W.K. Vanderbilt, Edward S. Meade, and Duncan Cryder, first became interested in the game and got the idea of building a course in the States. In 1889 I was engaged in laying out an 18-hole course at Biarritz, France. Biarritz at that time was a small village, and there were few tourists from America. I had nearly completed the Biarritz links when I met Vanderbilt, Meade and Cryder. They showed real interest in the game from the beginning; I remember the first demonstration I gave them. We chose the famous Chasm hole – about 225 yards and featuring a deep canyon which has to be cleared with the tee shot; I teed up several balls and laid them all on the green, close to the flag. Vanderbilt turned to his friends and said, “Gentlemen, this beats rifle shooting for distance and accuracy.” Soon afterwards these men asked me to come to America and build a golf course there. (“Early Courses of the United States,” Golf Illustrated, vol 41 no 6 [September 1934], p. 24)

Note, however, that when Dunn, in his older years, recounted self-aggrandizing stories of his contributions to golf history in the 1890s (as he does in this 1934 Golf Illustrated article), he was often inaccurate regarding details of dates, places, and people. In the case of the article quoted above, he gets many things wrong as he goes on to explain his role in the early development of the Shinnecock Hills golf course, but his anecdote about Vanderbilt and friends is accurate in marking the general trend in the 1890s of the shifting preference of America’s millionaire sportsman away from the fishing rod and the gun clubs to the golf club – a trend that is certainly observable in the history of the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club.

And not coincidentally, Dunn and Vanderbilt are part of the story of the earliest development of golf at Jekyll Island, for the latter was among the founding members of the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club in 1886 and the former was the designer of the club’s first nine-hole golf course in 1897.

Although Dunn’s claim that Vanderbilt brought him to Shinnecock Hills to design its original golf course is inaccurate, his claim to have enjoyed the friendship and patronage of Vanderbilt during his first years in America is accurate enough. Similarly, Dunn is inaccurate in suggesting that he built the first golf course at Jekyll Island “at the instance of Stanford White,” for White – the architect of the famous clubhouse at Shinnecock Hills – was never a Jekyll Island Club member (“Early Courses of the United States,” 25).

But Dunn also wrote that in addition to White, “several other New Yorkers, who owned hunting lodges on this Island,” invited him to design a golf course for the Club (“Early Courses of the United States,” 25). This claim is probably true. Dunn mixed up his millionaires – true to his working-class caddie roots in Scotland, he may have found it hard to tell one rich American from another – but he liked millionaires well enough and could easily tell them apart from non-millionaires.

Yet among the Jekyll Island millionaires, it is likely that Dunn’s commission to design and build a golf course at Jekyll Island arose from his connections not just with “New Yorkers” who were Club members, but also with those who were also members of the earliest golf clubs established in the American Northeast – and not just casual or social members of these clubs, but also owners, builders, presidents, golf captains, and committee chairmen.

At a high percentage of the early New York and New Jersey golf clubs in question, the designer of their golf courses had been Willie Dunn. As such, he was known by reputation to millionaire members of these clubs’ boards of directors, and yet he was also known to many of them personally through his work as the head professional at a number of these top golf clubs, ranging from Shinnecock Hills in 1893 to the Ardsley Casino Club in 1897. It was in 1897 that Dunn received the call from the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club to lay out its first proper golf course. But the beginning of golf on Jekyll Island actually predates by at least a year the construction of the Dunn course in question.

Jeckyll Island Golf Club Origins: A Mysterious Myth

Apart from inaccuracies in any tale told by Willie Dunn about golf in the 1890s, inaccuracies also abound in accounts by others of the beginnings of golf on Jekyll Island in the 1890s.

In “History of Golf in the Golden Isles” on the “Golden Isles Georgia” website, we read that “The Golden Isles' first official recognition as a golf venue came in 1894, when the Jekyll Island Golf Club was registered with the United States Golf Association” (https://www.goldenisles.com/history-of-golf-in-the-golden-isles/).

This claim cannot be true.

Technically, and perhaps trivially, since the U.S.G.A. was not known as such until 21 February 1895, it is impossible for the Jekyll Island Club to have been registered with it in 1894. The first national golf association in the United States was indeed formed in 1894, but it was first called the Amateur Golf Association and then for a few weeks in 1895 the American Golf Association.

Yet objection to the above claim about the first official U.S.G.A. recognition of golf on Jekyll Island involves more than a quibble about nomenclature.

To claim that the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club was registered in 1894 with the first national golf association formed on December 22nd, 1894, is virtually to claim that it is in the august company of the five charter members of the association at that late December meeting: Newport Golf Club, St. Andrew’s Golf Club, Chicago Golf Club, Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, and The Country Club in Brookline.

It was not.

Alternatively, since the New York newspapers had mentioned as early as October of 1894 that a meeting to organize a national golf association was planned for the end of the year, perhaps it is conceivable that the Secretary of the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club sent a letter applying for association with it sometime between December 23rd and December 31st.

He did not.

There was no golf course or practice facility for golf on Jekyll Island before the end of 1896, and there is no sign of interest in making golf one of the Club’s sports before this. As early as 1887 the Club had anticipated that it might take up horse racing, and so it indicated in its charter that it might “maintain a race course” on the island (an eventuality that never came to pass), but there was no mention of a golf course (Jekyl Island Club: Charter, Constitution, By-Laws and Members’ Names [New York: A.C. Cunningham, 1887], p. 4).

Yet the myth of an 1894 start for golf on Jekyll Island is out there.

In the essay “Golf, United States and Canada” in Sports Around the World (ed. John Nauright, Charles Parrish [Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2012]), John Nauright says that “The first southern club was the Swannanoa Golf Club in Asheville, North Carolina, which appeared in 1893, followed by the Jekyll Island Golf Club near Brunswick, Georgia, the next year” (Vol 3: “History, Culture, and Practice,” p. 240).

And there are other claims that refer to some sort of early official recognition of golf on Jekyll Island by the U.S.G.A.

In her account of the Jekyll Island Club in her article “Millionaire Village,” in Outdoors in Georgia (July 1977), Susan K. Wood takes the tack of revisiting Jekyll Island in the 1920s via “imagination,” and, in imagining club members playing the “oceanside” course designed in 1926 by Walter J. Travis, observes in passing that the Jekyll golf club “was only the thirty-sixth to be registered in the country, in 1894” (vol 7 no 7, p. 6). Similarly, in 3181: The Magazine of Jekyll Island, Charles Bethea writes that “The Jekyll Island Golf Club was chartered in 1894, the thirty-sixth in the nation” (“Closer to Nature,” 3181: The Magazine of Jekyll Island [Fall/Winter 2017], p. 56).

What of the new claim here that the Jekyll Island Club was the thirty-sixth golf club chartered by the U.S.G.A.?

The New York Times lists twenty-five golf clubs “Associated” or “Allied” with the U.S.G.A. at the time of the second annual meeting on 8 February 1896 (10 February 1896, p. 6). (The dues for Associate clubs were $100 per year; the dues for Allied clubs were $25 per year.) In The Golfer of March, 1896, the list of Associated and Allied clubs comprises thirty clubs (vol 2 no 5, p. 133). In neither item, however, is the Jekyll Island’s Sportsmen’s Club listed as either an Associated or Allied member, so it is clear that the Club was not registered with the U.S.G.A. before the spring of 1896.

Perhaps the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club was on the waiting list?

When the Golf Club of Lakewood invited golfers to play in its opening spring tournament in April of 1896, it advised potential competitors that “events are open to all members of the United States Golf Association, and, at the discretion of the Greens Committee, to the members of clubs that have applied for admission to the national union and are on the waiting list” (Sun [NY], 8 April 1896, p. 4). The new national golf organization was struggling to keep up with the emergence of fledgling golf clubs.

If the Jekyll Island Club was indeed the thirty-sixth golf club to have registered with the Association, this event must have happened between March of 1896 and May of 1897, for a report in the New York Sun states that at the U.S.G.A. Executive Committee meeting of May 6th, 1897, six new Allied golf clubs were admitted: thereby “The strength of the Association was increased to eighty-four clubs” (7 May 1897, p. 5, emphasis added)

Golf Club Versus Golf Course

In considering this question about the beginning of golf on Jekyll Island, one must use terms precisely and bear in mind the important distinction between the concept of a golf “club” and the concept of a golf “course.”

A golf course is a piece of land, a geographical location fixed on the earth. A golf course does not change its location: course and location are identical.

A golf club, however, is a social and (when incorporated) legal organization of people, and so a golf club can change its geographical location without becoming a different club. Golf clubs often move from one piece of land where golf is played to another, as conditions may require or suggest. In Scotland today, for instance, some of the oldest golf clubs in history find themselves playing on land not just remote from where the club began to play, but also on layouts developed hundreds of years after the club was formed.

And so a golf club may be the same age as the golf course upon which it plays golf, or it may be older or younger than the course on which it happens to play the game at any particular time.

Note also that many a golf club has been founded before it even built or located a golf course on which to play.

That the Jekyll Island Club had no golf grounds before 1896 does not necessarily mean that it had not formally declared itself a golf club before 1896. Theoretically, for instance, it could very well have registered as a golf club with the U.S.G.A. before its first golf course was built (although this seems unlikely)

First Golf

Apart from the question of when golf was recognized by the U.S.G.A. as one of the sports of the Jekyll Island Club, there is the more interesting question of when golf clubs first struck golf balls on the island?

John Companiotte writes in A History of Golf in Georgia that “While the first golf course at Jekyll Island did not open until 1899, the wealthy residents who built large cottages there certainly played golf before then, hitting balls on the lawns” (12). Details here are incorrect. As we shall see, the year 1897 – not 1899 – is when the first golf course opened on Jekyll Island. And the earliest golf was probably not played on the cottage lawns, which were smaller and much closer together than Campaniotte might have imagined, but rather on open ground north of the clubhouse and cottages. The lawns of the clubhouse and cottages were landscaped early and relatively densely with gardens, hedges, and trees, inhibiting anything but chipping and putting practice by the mid-1890s when golf had gathered some devotees among the Jekyll Island Club members. Without risking harm to persons or property, no one could have swung a club at a ball with full force within the Jekyll Island clubhouse “enclosure” or “compound” (as the area of clubhouse, cottages, and related buildings that was surrounded by a fence to keep out wild animals was called).

Figure 3 Richard T. Crane, circa 1920s. In Tyler B. Bagwell and Tyler E. Bagwell, The Jekyll Island Club (Mount Pleasant, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 1998), p. 74.

But Companiotte is no doubt correct that golf was played on the island in some form before a proper golf course was built. Devoted golfers have always taken whatever opportunities are available to them to practice their short games in unusual places.

We see in the photograph to the left that even relatively late in the history of the Jekyll Island Club, when it boasted an excellent eighteen-hole layout, one of the long-time members, Richard T. Crane, was photographed practising his putting on a path running across his lawn. Yet there was a proper putting green dedicated for just such practice less than a mile from where Crane stood!

As we shall soon see, it turns out that a year before Willie Dunn built a nine-hole golf course on Jekyll Island, there had already been a golf “convenience” built for the earliest of the Club’s ardent devotees of the ancient game.

First Golfers

What do we know of the mid-1890s interest in golf among the first generation of Jekyll Island Club members, apart from Vanderbilt?

Several Jekyll Islanders were golf mad by 1895. In January of 1895, Arthur B. Claflin (a Club member since 1889) was in the gallery of a large crowd following a match at the Golf Club of Lakewood, New Jersey, between the club’s professional golfer and a visiting professional golfer named Samuel Tucker, the nephew of Willie Dunn.

In December of 1895 (the year in which he joined the Club), George J. Gould donated a silver loving cup as a prize for competition at the same Golf Club of Lakewood where Claflin was in the gallery eleven months before, and a few days later Gould bought the land where within months he would have 1895 U.S. Open winner Horace Rawlings build a nine-hole course for a rival club, the Ocean County Hunt and Country Club.

While Claflin and Gould were at the center of golf developments in Lakewood, original Jekyll Island Club member William Bayard Cutting, Sr, hired Willie Dunn in the spring of 1895 to lay out a private nine-hole golf course for him at his country estate called Westbrook, on Long Island.

By then, fellow original Club member J. Pierpont Morgan had already had a shorter practice course of his own laid out on his estate at Cragstone on the Hudson River.

Any of these golf-mad Club members (or perhaps golf-mad members of their families, particularly sons and daughters) might have brought golf clubs south to Jekyll Island by the mid-1890s and hit balls about in the open ground north of the clubhouse compound. If some of them did so, they may even have selected an area of open ground where they could plant flagpoles to mark out a rudimentary golf course.

In fact, the history of the beginnings of golf in North America is rife with accounts of just such practices: individuals and small groups of people fashioning rudimentary golf courses of three, four, or five holes in open fields near their homes or places of business. Such is the origin of many a community’s first golf course, which was often simply referred to as a “links,” “golf field” or “golf ground.”

See the images below of the primitive golf course laid out in the early 1890s at Camp Le Nid on the shores of the Bay of Quinte on Lake Ontario by Walter S. Herrington, leader of a summer camp where 1883 law graduates from Victoria College gathered annually from all across North America for rest and recreation.

Figure 4 Camp Le Nid Golf Links, Bay of Quinte, Ontario, circa mid-1890s. Photograph item N-02691 (left) and photograph N-11016 (right) reproduced courtesy of the County of Lennox and Addington Museum and Archives.

The fairway is a field “mowed” by cattle or sheep. The green is a circle of pasture grass cut low to a diameter of three feet, with a hole at the center marked by a small pole and plaque. Over the shoulder of the man putting in the foreground we see a man finishing play at the previous hole not far away. The tee at each hole is marked by a small flag-topped pole stuck in the ground, seen to the right of the man waiting to tee off in the photograph above on the right.

Camp Le Nid Golf Links was not much of a golf course, but It sufficed as a starter course for the golf pioneers in that area.

Something like the sort of rudimentary, provisional golf course we see in the photographs above may have been set up on Jekyll Island by the mid-1890s whenever two or more of Jekyll Island’s early ardent votaries of the ancient game gathered in golf’s name.

A Golf Convenience

The first indication that there was an actual area on Jekyll Island dedicated to golf comes in a newspaper article that points to 1896 as the year when golf was officially recognized as one of the sports of the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club.

The Morning News of Savannah reports at the end of December of 1896 on busy preparations for the 1897 season: “On Jan. 15 the Jekyl Island Club will open for the reception of guests. Preparatory to the season’s round of pleasure, the finishing touches are being put on the grounds, club house and apartment cottages” (29 December 1896, p. 6). A particular aspect of this work stemmed from the fact that earlier in 1896 the Club’s Executive Committee had approved plans for development of a golf facility at Jekyll Island:

The club house season will begin on Jan. 15, but the cold weather north has caused an advanced guard of millionaires to seek the genial climate off Georgia’s coast….

The younger set will take much more interest in the club this season than for many past. The necessity for having this so was made plain to the executive committee many months ago, and plans for bringing it about started.

The completion of extensive improvements … was the vital point accomplished…. A remodelling and enlargement of the ballroom … [and] improvements in the billiard and pool room, stables and equipments, and conveniences for water sports, tennis, golf, etc., have added all that is desirable for the young” (11 January 1897, p. 3).

For the sake of “the younger set,” lo and behold, there was a “convenience” for golf ready by the beginning of the 1897 season!

Locating the Golf Ground

In the photograph below, we see a field marked by a sign reading “Golf Ground."

Figure 5 Undated photograph from William Barton McCash and June Hall McCash, Jekyll Island Club: Southern Haven for America's Millionaires (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1989), p. 46.

There are no identifiable golf course artifacts visible in the photograph: no tee boxes, no flagpoles, no putting surfaces. It is possible that this undated photograph of an apparently minimalist ground for golf is in fact a photograph of the “convenience” for golf built in 1896.

Along the left side of the photograph is River Road, running north and then curving slightly eastward in the distance. River Road ran along the west side of the island with Jekyll Creek and the tidal marshes to its left and open ground to its right. It was built by the Jekyll Island Club shortly after the formation of the club. To the east, running parallel to River Road for about three miles, was one of the oldest roads on the island, Old Plantation Road. Land to the east of Old Plantation Road was largely forested.

For about a mile, these roads ran north of the clubhouse enclosure about 100 to 130 yards apart until they reached Captain Wylly Road, which intersected each of them on a generally east-west axis, at which point they gently turned northeast and continued to run parallel, still about 100 to 130 yards apart, for about two miles, at which point they converged several hundred yards beyond Horton House (familiarly known as “the old Tabby House”).

Occasionally, a short road ran perpendicularly across the generally open ground between them – one of which can be detected at the very bottom of the photograph above.

On the left of the photograph we can see the scrub brush that formed between River Road and the tidal marsh along the west side of the north part of the island. On the right of the photograph we can see the forest that was on the east side of Old Plantation Road. In the far distance, we can see signs of a line of trees between River Road and Old Plantation Road: they may mark one of the roads that ran between them, where what we might call “tree fences” grew up or were planted over the years, informally segmenting the land between River Road and Old Plantation Road into distinct fields (unfenced).

In the foreground of the photograph above is a rack for parking the bicycles, which had just recently become a ubiquitous part of island life. Tyler B. Bagwell and Tyler E. Bagwell say that “By the 1890s bicycles were the island rave” (The Jekyll Island Club [Mount Pleasant, S. C.: Arcadia Publishing, 1998], p. 68). Near the end of the 1897 season, a newspaper report introducing readers to the Jekyll Island Club brought its concluding focus to the topic of this new bicycle rave:

Jekyl Island is owned by a club of wealthy men, who go there at intervals for rest. The place which is known as “Millionaires’ Island” contains fourteen hundred acres laid [out] in lovely parks and drives, with fifty-one miles of the most beautiful shell roads for carriages and nearly twice that distance in bridle paths, with ten or fifteen miles of the most perfect wheel roads in the world, for nearly everyone on the island, old and young, has a bicycle. Indeed … nearly all of them [have] two wheels [that is, bicycles] that they might be sure to have one of them always in readiness for use. (Huntsville Weekly Democrat [Alabama], 31 March 1897, p. 2)

William Rockefeller said, “The bicycle craze is extending, and no telling where it will end” (McCashes p. 50). Bicycle paths were paid for by Jekyll Islanders like Rockefeller himself – and named accordingly.

Figure 6 The Rockefeller bicycle path, dating from the early 1900s, was located on the east side of the island.

In the background on the right side of the photograph of the “Golf Ground” several pages above, we can just make out a light-coloured fence and the bottom part of a light-coloured building.

Figure 7 A detail from the photograph above of the golf ground.

The building in question is obscured by the bottom right edge of the sign. There were many such whitewashed buildings around the island dedicated to various functions: the mule shed, stables for horses, farmhouses and hen houses, laundry buildings, and so on. Most of them had a white fence associated with them.

Figure 8 White buildings on Jekyll Island in the early 1900s. Left to right: laundry; farmhouse and barn; mule shed.

The number and variety of these buildings proliferated over the years. As early as the first season (1888), for example, it was necessary for the Club to build a house for the gamekeeper’s assistant (McCashes p. 21).

The best clue to the location of the “Golf Ground” is the crossroad between River Road and Old Plantation Road that appears at the bottom of the photograph of the “Golf Ground.” It suggests that the “Golf Ground” was located at one of three locations: (i) the unnamed crossroad on the north side of Hollybourne Cottage, (ii) the part of Captain Wylly Road that crossed between River Road and Old Plantation Road, or (iii) the crossroad named Palmetto Road.

The fence and white building in the photograph could be associated with the area alongside Old Plantation Road known as “the Plantation.” If so, the photograph of the “Golf Ground” would seem to have been taken at the intersection of River Road and Captain Wylly Road.

Support for this possibility comes from the fact that the photograph shows River Road bending slightly toward Old Plantation Road, just as it did in the Club’s days as it ran north from its intersection with Captain Wylly Road.

Island Landscape North of the Clubhouse

The state of the land on the west side of the island running north between River Road and Old Plantation Road alongside Jekyll Creek and its marshes is described in an article written in 1897 by John R. Van Wormer, who was a guest on the island in January of that year: “To the north [of the clubhouse], for the space of a quarter of a mile from the bank of the creek, are open ground, cultivated fields, quail meadows, with a scrub palmetto growth fringing the shore and marsh; the gamekeeper’s house, the kennels, the pheasant pens, and stretching north and west, forest, vale and marsh” (“An Island on the Georgia Coast,” The Cosmopolitan, vol 24 No 3 [January 1898], p. 293).

The open ground that Van Wormer describes is shown on a map published in 1893 as part of the Thirteenth Annual Report of the Geological Survey for 1891-92.

Figure 9 Jekyll Island before construction of Jekyll Island Club clubhouse or the du Bignon house, as seen in a detail from a map in the Thirteenth Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey for 1891-92, which was published in 1893. The "open ground" described by Van Wormer is shown above within the orange line I have drawn on the map. This “open ground” is three miles long, and “a quarter of a mile” wide from “scrub palmetto growth” along the shore (of creek and marsh) to the woods on the east side of Old Plantation Road.

The survey from which the map was produced in the early 1890s no doubt dates from several years earlier, as the Clubhouse does not appear on the map, nor does the du Bignon house built in the early 1880s. The only structures marked on the map seem to be Horton House at the north end of the island, the western-most part of what will become Captain Wylly Road, and Old Plantation Road, which runs from Horton House south to Wylly Road but does not yet even reach the open area where the Clubhouse would be built.

Note that in describing what one encounters along the Jekyll Creek side of the island as one proceeds from south to north, Van Wormer not only describes the area in detail, but also describes it in order: first, you encounter “open ground, cultivated fields, quail meadows”; second, at the end of the relatively open area, you encounter “the gamekeeper’s house, the kennels, the pheasant pens”; finally, “stretching north and west” from the gamekeeper’s compound, you encounter “forest, vale, and marsh.”

We can consider the nature of each of these areas below – in order.

Open Ground

The original state of the flat, relatively treeless ground where the cottage compound was located, at the northern end of which the Maurice cottage would be built, is suggested in the photograph below, which is an 1887 view looking northeast from south of the newly built clubhouse and the du Bignon house – the only two buildings that existed in this area at the time.

Figure 10 The open ground stretching north from the clubhouse along the west side of the island was flat, with a slightly rougher landscape along the shore of Jekyll Creek and the tidal marsh. This photograph from 1887 is taken from near the shore of Jekyll Creek looking northeast.

A few years after the photograph above was taken, Charles Stewart Maurice built the house that would mark the northern limit of the clubhouse compound until the 1920s. In 1888, McKevers Bayard Brown had built a cottage along the edge of Jekyll Creek in the open ground north of the clubhouse (it was the first cottage built on the island), but since it was located so far from the clubhouse, it could not be enclosed within the compound. The Maurice house, completed in 1890, was initially called “the famous Maurice cottage, ‘Les Trois Pin[s]’” [The Three Pines] in a Georgia newspaper (perhaps because some Georgians thought of it as “the French chateau of the Maurice family”), but it has traditionally been known as Hollybourne Cottage (Morning News [Savannah, Ga., 19 January 1896, p. 12; William S. Irvine, Brunswick and Glynn County, Georgia [Brunswick, Ga.: Board of Trade, Brunswick, 1902], pp. 18-19).

The flat, open ground on which the cottage was built, as well as a glimpse of the flat, open ground beyond the cottage to the north, is visible in one of the earliest photographs of it.

Figure 11 The Maurice house Hollybourne Cottage circa 1890. The photographer looks from south to north at the back of the house. The front of the houses faces west, toward the pine trees and Jekyll Creek on the left side of the photograph. Past the right side of the house, once catches a glimpse of the open ground that runs uninterrupted up to the trees at Captain Wylly Road well to the north.

Twenty years of tree growth north of Hollybourne Cottage can be seen in the photograph below.

Figure 12 A detail from Jekyl Island Club (1911) shows the view north from the clubhouse tower. River Rd and Old Plantation Rd run north and cross Captain Wylly Rd. The employees’ residence known as “The Quarters” can perhaps be made out on the right.

Similarly, a sketch of the brand new McKevers Bayard Brown Cottage (at the edge of Jekyll Creek and its marshes) reveals in the background the “quarter of a mile” band of treeless grassland that Van Wormer described as stretching from the shore of Jekyll Creek and its tidal marsh to the forest east of Old Plantation Road.

Figure 13 A sketch of the cottage of McKevers Bayard Brown from 1888, and a photograph of the cottage from a couple of years later, each show the open ground behind the cottage.

The treeline of the forest that runs northward on the east side of Old Plantation Road is visible in the background of both images above. The drawing appeared in Scientific American as an example of the work of architect William Burnett Tuthill (vol vi no [July 1888], p. 1). It is likely that the drawing was sketched from an actual photograph of the house like the one on the right and that the depiction of the flat, open ground behind the house is as accurate as the depiction of the house.

Fields

The “cultivated fields” that Van Wormer mentions may have been a legacy of the work of the first gamekeeper, W.A. Dolby, who had been brought to the island from Yorkshire, England, in part because of his expertise with the non-native English pheasant that the Club hoped to establish on the island.

His 1887 report to the superintendent of the Jekyll Island Club had recommended certain measures for the open ground:

Jekyl Island offers unusual facilities for the preservation of all descriptions of game …. Winged game of most kinds can be raised in unlimited numbers at small cost, as natural feed abounds in great profusion, whilst the open ground can be cultivated and planted with such crops as millet, buckwheat, cow peas, broom corn, turnips, etc., that will afford all that is necessary for their maintenance in very large quantities. (“Report of Supt. Ogden: To the Board of Directors Jekyl Island Club, in Jekyl Island Club: Charter, Constitution, By-Laws and Members’ Names [New York: A.C. Cunningham, 1887], p. 7).

Dolby seems to have acted quickly on these plans for cultivated fields. In the same month that Dolby submitted his recommendations, the Morning News of Savannah reported on preparations for making a habitat hospitable to quail: “with a view to their support and propagation, fields have been cleared and sown with grain” (12 December 1887, p. 3).

On January 16th of the same year, the Jekyll Island Club “treated … with genial cordiality,” and “gave … the freedom of the island for shooting,” to a “sportsman tourist” who sailed to the island while the clubhouse was under construction (“the brick walls are already up to the fourth story,” he observed), and when this tourist was told by Dolby of his plans, he expressed skepticism:

The Jekyl Island Club proposes … to stock the island with quail, a project which may succeed if the quail do not prefer to leave for the mainland, as very likely they may. I much doubt if they will find the requisite food here; and I could not repress a rather broad smile at the proposition of one gentleman, to sow buckwheat at various points on the island to “feed the birds.” I hope he may live to see a bushel of buckwheat raised on any island between Savannah and Key West. When that happens, we shall raise fine crops of bananas on Cape Cod. (Nessmuk, “Unofficial Log of the Stella, II,” Forest and Stream, vol 28 no 1 [3 February 1887], p. 22).

Almost ten years to the day later, Van Wormer writes of “cultivated fields” north of the clubhouse.

The late 1890s photograph below shows a couple on what I take to be Old Plantation Road; they are walking southward in the direction of the Clubhouse compound (presumably after a morning hunt), with long grasses filling the flat land stretching west of them toward River Road.

Figure 14 Tyler Bagwell, Jekyll Island: A State Park (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001), p. 64

In 1897, the Club’s Executive Committee expanded on Dolby’s ambitions, approving supplementary grain growing plans for land known as the “savanna” east of the Clubhouse, “such that a tide-gate [was] … built in the ditch at Shell Road in 1898 ‘to enable the planting of upland rice and other bird food cereals’” (See James S. Brunner, “Jekyll Island Golf History – The 1910 Donald Ross Course,” June 1998, U.S.G.A. Archives, p. 2).

Quail Meadows

One of the “quail meadows” to which Van Wormer refers appears in the photograph below.

Figure 15 A hunting party returns south to the clubhouse circa 1890. McCashes, p. 43.

In the photograph above, the success of the hunting expedition organized by Club member William Struthers around 1890 is indicated by the birds swinging in the hands of the hunters. Perhaps we can see why these open grounds were jealously protected by the Game Committee when in 1897 a proposal was made to use this part of the island for development of a golf course. At the same time, a golfer can look at this photograph and see why Club members looking for a site for a golf course would have been interested in the gently undulating ground of such a meadow.

The Gamekeeper's House

According to Van Wormer, beyond the quail meadows were the gamekeeper’s house, the kennels, and the pheasant houses.

Were these buildings all grouped together, or were they distributed from south to north like the other parts of the open ground that Van Wormer describes?

Tyler B. Bagwell and Tyler E. Bagwell locate the gamekeeper’s house at the area to become known as “the dairy” as of the early 1900s: “three employee houses, adjacent to the dairy, were used by the gamekeeper, assistant gamekeeper, and the dairyman” (The Jekyll Island Club [Chapel Hill, N.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 1998], p. 114).

The photograph below seems to show the gamekeeper’s house and grounds around 1903.

Figure 16 The four figures seen on the road above, circa 1903, are probably gamekeeper Charles Brinkman and his three children: Conrad (aged seven), Carl (aged six), and May (aged three).

A photograph in the Charles Lanier book Jekyl Island Club (1911) may show the gamekeeper’s pheasant houses and kennels on the open ground where Jasmine Road crosses from River Road to Old Plantation Road. Jasmine Road ran on an east-west axis alongside a stream that crossed Old Plantation Road and then River Road before emptying into the tidal marsh located between the west shore of Jekyll Island and the open water of Jekyl Creek. Jasmine Road is marked clearly on an early 1920s Club map of Jekyll Island.

Figure 17 Jasmine Road is circled in purple on the left side of the map. The word “Dairy” is printed in the center of the map. Brown Cottage is marked with a purple dot. Hollybourne Cottage is circled in purple at the north end of the clubhouse compound, as are "The Quarters." Map found in Brunner, n.p.

The same stream still flows today, rising in a swampy area on the east side of the island and flowing west to the tidal marsh, crossing the same two roads along the way. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, however, Jasmine Road extended further east than the above map shows, running right into the center of the island. Today, the part of Jasmine Road that crossed between River Road to Old Plantation Road no longer exists, but the part of Jasmine Road than ran east from Old Plantation Road toward the swampy pond where the stream in question arose still exists. It is an unnamed dirt road that follows the same stream that Jasmine Road paralleled, as shown in the photographs below.

Figure 18 Left: "Jessamine Road" as shown in Jekyl Island Club (1911); right: a contemporary image from the same vantage point as shown in the photograph to the left.

The photograph below is labelled “Jessamine Road” in Jekyl Island Club (1911).

Figure 19 "Jessamine Road" in Jekyl Island Club (1911). The photographer looks from River Road toward Old Plantation Road.In the far distance, three figures can be seen, perhaps the people who have just trimmed the hedges. In the top left corner of the photograph is a building with columns supporting a gable roof, along which a gutter running to a downspout.

The photographer looks along Jasmine Road from River Road toward Old Plantation Road. In the upper-left corner of the above photograph, one can see a substantial building, perhaps part of the gamekeeper’s compound of pheasant houses and kennels.

As I shall suggest in sections to follow, the compound of kennels and pheasant houses seems to mark the northern end of the first nine-hole golf course built on Jekyll Island.

Rating the Golf Convenience

For the most part, silence prevails in evaluation of the “convenience” for golf built sometime in 1896.

Was it more than a pitching and chipping area? Was it more than a glorified driving range?

One presumes that the golf “convenience” will have had at least a few poles stuck in the ground to mark out some golf holes. Golfers need something to aim at. The teeing area, as according to the original rules of golf, could simply have been a spot within a club-length of the hole. Such was the case with many a rudimentary golf course in North America in the 1890s.

For the sake of comparison with one of the earliest golf courses in the South, consider the photograph below of the Swannanoa golf course (Asheville, North Carolina) in one of its 1890s iterations. It was no more than an open field with flags stuck in the ground.

Figure 20 Swannanoa Golf and Country Club, Asheville, North Carolina, circa mid-1890s.

The woman in the foreground, attended by her caddie, has finished play on the fifth hole, marked by the short white pennant-flag behind her. She tees off from an area close to the hole at which she has just putted out. At the bottom of the hill (at the bottom right corner of the photograph), another golfer, also attended by a caddie, having completed the fourth hole (marked by a nearby flag), prepares to drive up the hill to the fifth hole. Other golfers and other flags are also visible in the same field.

It is easy to imagine that the golfers who used the golf “convenience” did something similar. Flags to mark holes may have been placed in the field only when people arrived at the Club who were interested in knocking golf balls about. If early ardent votaries of the ancient game did this sort of thing during the 1897 season, then the “convenience” for golf that the Executive Committee ordered to be built in 1896 would technically count as the first golf course on Jekyll Island.

Has anyone left to posterity an evaluation of this “convenience” for golf?

Or, is silence about it an implicit evaluation?

Van Wormer wrote his article during the summer of 1897 having visited the island in January of that year. For all his detail in describing the open ground north of the clubhouse, he does not mention a golf ground or a golf field, let alone a golf course. He may not have noticed it, especially if there were no flags installed to mark golf holes.

Or perhaps in the context of his determination to celebrate the magnificence of what the Jekyll Island Club had accomplished – “At the landing on Jekyl Creek, one debarks from the club steamboat at a wellbuilt dock which terminates in a vista of trees. Opening out in wide prospect beyond is a fairy scene” – Van Wormer decided that the paltry “Golf Ground” was not worth mentioning as part of such a scene.

If so, Van Wormer’s silence about the golf “convenience” is implicitly the first review.

It is also interesting to note that according to the Atlanta Constitution, Robert Todd Lincoln (a devotee of golf) was a guest at the Jekyll Island Club in March of 1897: “Robert T. Lincoln, the son of Abraham Lincoln, passed through the city last night with a party on a trip to Jekyl Island. The party will spend about two weeks on the famous little island and expect to have a great time down there” (12 March 1897, p. 8). His visit was just after the original “convenience” for golf was introduced but before the Willie Dunn course was built at the end of 1897.

The eldest son of President Abraham Lincoln and Mary (Todd) Lincoln, he was born in Springfield, Illinois, in 1843, graduated from Harvard before the end of the Civil War, served on the staff of Ulysses S. Grant as a captain in the Union Army, married the daughter of a U.S. senator, completed law school in Chicago and then practised law there. In due course, he accepted appointments as secretary of war (1881-1885) in the administrations of Presidents Garfield and Arthur, and he was then appointed U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom (1889-1893) during the Benjamin Harrison administration.

So of course as Lincoln and his entourage passed through Atlanta on their way to Jekyll Island, the reporter for the Atlanta Constitution asked him for his opinion on the prospects of the new administration of President William McKinley (who had been inaugurated president exactly one week earlier), and of course Lincoln offered a diplomatic response. Informing us that “Mr. Lincoln never took any prominent part in politics until he was given a cabinet portfolio by President Garfield in 1881 …, and there made a reputation which will ever do him honor,” the reporter explains that “Mr. Lincoln would say nothing more concerning politics other than that he was pleased with the McKinley administration and thought that prosperity and good times were ahead” (12 March 1897, p. 8).

Figure 21 Robert Todd Lincoln playing golf in the early 1900s in the U.S. northeast where he maintained a summer home.

Less than four years before his 1897 visit to Jekyll Island, Lincoln had been introduced to golf by Charles Blair Macdonald, a leading figure in early American golf as both a player and a golf course designer. Macdonald invited Lincoln to join a group of men in July of 1893 to organize the Chicago Golf Club, which had the first eighteen-hole golf course in North America. Knowing nothing about golf, Lincoln nonetheless accepted this invitation and became one of the golf club’s founding members.

When Macdonald introduced him to golf, Lincoln was fifty. Perhaps he was too old to have become a scratch golfer, but he quickly developed proficiency at the game by taking lessons from Macdonald (who was one of the top two or three amateur golfers in the game at the time) and Jim Foulis, Jr, the Chicago club’s resident professional golfer and the winner of the second U.S. Open championship (1896).

By the time Lincoln first visited Jekyll Island in March of 1897, he had became quite enthusiastic about the game and was sufficiently popular as the celebrated son of the former president to have been frequently invited to play with top amateur and professional golfers, despite his merely average skills.

Lincoln cut short his visit to Jekyll island in March of 1897. The Morning Times of Savannah reported that he was in Atlanta the evening of March 11th, apparently travelling to Jekyll Island on Friday, March 12th : they expect “to spend about two weeks on the famous little island and expect to have a great time down there” (12 March 1897, p. 8). In the event, the Morning News reports, Lincoln left the island on Thursday, March 18th – after just five full days on the island (21 March 1897, p. 12).

Did he not “have a great time down there”? If not, was an inadequate “Golf Ground” the occasion of his disappointment?

Many years later, Lincoln actually commented on golf facilities at Jekyll Island: “[Jekyll Island] is a very pleasant place, but in one particular it is not what I want as a Winter Resort; that is, in the matter of golfing. There is, it is true (or was) a place where one could make a pretence of knocking balls about, but it was not at all interesting as a golf course” (Robert Todd Lincoln letter to Cyrus McCormick, 14 February 1911, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, cited by William Barton McCash, Southern Haven, p. 47).

Whether or not Lincoln refers to the 1896 “convenience” for golf in this criticism is not clear, for Lincoln had also since visited the island in 1902, when the “convenience” for golf had been replaced by a golf course built by Willie Dunn. But if Lincoln had not in fact been able to play golf on his 1902 visit to the island, his derogatory comments about the Club’s golf facilities may well have been about the golf “convenience” built in 1896.

Note, by the way, that if the photograph above of the “Golf Ground” is indeed a photograph of the “convenience” for golf built in 1896, such nomenclature does not necessarily insult the golf facility as unworthy of the name of “golf course.” When people described land on which golf was played in North America in the 1890s and early 1900s, the phrase “Golf Ground” was used interchangeably with the phrases “golf course,” “golf links,” and “golf field.” Early newspaper writers simply treated the area where golf was played as analogous to a cricket ground or a baseball field. For instance, when the Brooklyn Daily Eagle announced that William Bayard Cutting, Sr, was having a very expensive private golf course built by the best designer in the land, Willie Dunn, the headline was: “Bayard Cutting’s Golf Grounds” (24 May 1895, p. 7).

Jekyll and Hyde

So the first “golf course” on Jekyll Island may have been a golf ground of a very rudimentary nature. It was probably not much more than a field dedicated to golf with flags planted here and there as targets. Although such a field might have proved to be uninteresting as a golf course for experienced golfers, it was better than nothing, and it was obviously offered merely as the first response of the Executive Committee to pressure put upon it by certain Club members to do something to make possible the playing of golf on Jekyll Island.

We know that the Executive Committee felt this pressure in 1896. As articles in the Savannah Morning News at the beginning of January of 1897 indicate, much earlier than this there had been some sort of approach to the Executive Committee by certain Jekyll Island Club members requesting that “conveniences” for certain sports be built on the island in order to interest the younger generation in vacations at the Club: “The necessity for having this so was made plain to the executive committee many months ago” (11 January 1897, p. 3, emphasis added).

Who was on the Executive Committee that was told to get moving on this project?

According to the constitution of the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club, there would be an annual shareholders meeting on the second Wednesday of June each year. Shareholders would annually elect as officers of the Club a President, a Vice-President, a Secretary, and a Treasurer. Shareholders would also annually elect a Board of Directors of thirteen Club members. Directors would elect an Executive Committee to consist of five members, two of which were to be the President and Treasurer, the other three being Directors. The Morning News informs us that the Executive Committee for 1896-97 comprised President Henry E. Howland, Secretary Frederic Baker, Treasurer D.H. King, Jr, Cornelius N. Bliss, and Henry B. Hyde (13 January 1897, p. 6; see also the New York Times, 4 October 1896, p. 33).

The Morning News also indicates that “Bliss and Hyde are very active in club affairs. Both are on the Executive Committee as well as the committee on purchases and supplies” (2 January 1897, p. 2). Henry Hyde seems to have been the member of the Executive Committee who took charge of the matter of arranging for a golf course to be developed on Jekyll Island. June Hall McCash notes that Hyde was the one “seeking to raise funds for the first Jekyll Island golf course” (Jekyll Island Cottage Colony [Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1998], p. 118). He wrote to fellow Executive Committee member Treasurer Frederic Baker about some of his preliminary conversations with regard to funding any such project via subscriptions: "I have talked the matter over with Mr. Pulitzer and Mr. McKay. My idea was to raise $10,000. I think Pulitzer would have given two or three thousand and Mr. McKay would have been very liberal” (Hall McCash p. 118, note 25).

Figure 22 Statue of Henry B. Hyde in the Metropilitan Museum of Art, New York City

Hyde was the prime mover and shaker in the Club at this time, supported by Baker and King. William Barton McCash and June Hall McCash refer to the three members as “the Hyde-Baker-King coterie” (Jekyll Island Club: Southern Haven for America’s Millionaires [Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1989], p. 85). A Club member referred to Hyde’s personal network of supporters within the Club as “the machine” (McCashes p. 85). June Hall McCash describes him as “the executive committee member who had taken control of club affairs” (p. 86). It was Hyde who had the most at stake, then, when Henry Howland gave up the presidency in 1897, to be replaced by Charles Lanier – “handpicked by Hyde and elected without opposition” (McCashes p. 85). Hyde’s machinations had succeeded, and, as expected, Lanier “endorsed the plans Hyde was then promoting for improvements at Jekyl” (McCashes p. 85).

And as of 1896, we know, Hyde’s plans for improvements included a “convenience” for golf.

Golf course design and construction for the Jekyll Island Club seems always to have been via the kind of subscription plan that Hyde began to work on around 1896. Constitutionally, the Executive Committee would have been responsible for building a golf course, but it was not allowed to incur significant debt in fulfilling this responsibility.

On the one hand, the constitution indicates that the Executive Committee “shall have the management and care of all the real estate, waters, buildings, live stock, game, improvements, fixtures, and all other property of every kind and nature, belonging to or controlled by the Club,” and it also indicates that it “shall have the sole power of making purchases and sales of every description, excepting real estate,” but, on the other hand, “in no case shall [it] contract debts or incur any pecuniary responsibility in any one year, to exceed one thousand dollars, over and above the annual income of the Club from yearly dues and entrance fees” (Article V, items 2, 4, and 4, respectively, in Jekyl Island Club: Charter, Constitution, By-Laws and Members’ Names [New York: A.C. Cunningham, 1887]).

Generally, then, the big projects of the Jekyll Island Club were funded by subscriptions – projects including not just golf courses and tennis courts, but additions to and renovations of the clubhouse, preservation of Horton House, construction of Faith Chapel, and so on. By the 1920s, as the McCashes point out, “club members were expected to support a variety of subscriptions” (p. 122). Furthermore, maintenance of big new “conveniences” for sports was financed by subscription. The Donald Ross course built in 1909 subsequently proved costly to maintain, and its maintenance costs were covered by subscriptions, leading Almira Rockefeller to complain about inequities in this method of financing: “The golf course is a great expense and kept up by voluntary subscriptions. We never use it but pay more for its upkeep than many” (McCashes, p. 54).

Jekyll Island Club records at the Jekyll Island Museum show that Henry Hyde maintained many of these subscription lists, confirming the 2 January 1897 report in the Morning News that he was “very active in club affairs” (p. 2). The same article that tells of Hyde’s work for the Club also mentions the “necessity” “made plain” to the Executive Committee that there be immediate work on building “conveniences for water sports, tennis, golf, etc.” (p. 2, emphasis added). The word “conveniences” comes right out of Article V, item 3, of the constitution of the Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club which describes the “Powers and Duties of the Executive Committee”: “They shall make and enforce all needful and proper rules and regulations for the care, improvement and maintenance of the real estate, waters, buildings, fixtures and conveniences of the Club” (p. 11, emphasis added). Such language in the newspaper may indicate that it was Hyde himself (a member of the Executive Committee, a member of the committee on purchases and supplies, and so a person “very active” in Club afffairs who would have been well-versed in the Club’s constitution) who spoke to the reporter for the Morning News about the topic of “major improvements” undertaken by the Executive Committee (2 January 1897, p. 2). That is, we may hear an echo of Hyde’s own words in the reporter’s words.

Recall that the Morning News indicates that as soon as “the necessity” of building “conveniences for … golf” was “made plain” to the Executive Committee in 1896, “plans for bringing it about started” (11 January 1897, p. 3). From the look of the “Golf Ground” in the photograph above, we can conclude that it would not have cost $10,000 to make such a golf “convenience.” Approximately the same amount of money was raised more than a decade later for the design and construction of the nine-hole Donald Ross course in 1909. Hyde’s discussion of a subscription plan clearly had in view a state-of-the-art ninehole golf course, not a mere field where one could make a pretense of hitting balls about. Presumably the Executive Committee undertook the construction of a “convenience” for golf as a temporary, shortterm way to address the need for a golf course that had been “made plain” to it. Such a facility was perhaps all that could be built in short order before an official, long-term plan could be formally agreed upon and financed.

Golf-Mad Jekyll Islanders

The New York Sun announced in January of 1898 that golf had arrived at Jekyll island:

The Jekyll Island Sportsmen’s Club, probably the most noted gunning and hunting organization in the South, has taken up golf.

It is about the greatest victory accomplished by the game in its missionary progress over the American continent. An inclination in favour of the game amongst its members … is back of the adoption of golf by the club. (16 January 1898, p. 8).

A prime list of some of the most notable Club members with “an inclination in favor of the game” has already been offered: George Jay Gould, John Pierpont Morgan, Sr, William Bayard Cutting, Sr, and Arthur Brigham Claflin.

They are the prime suspects with regard to the question of which club members might have communicated to the Executive Committee the “necessity” of including golf facilities among the new “conveniences” for sport to be constructed during 1896.

George Jay Gould

Figure 23 George J. Gould in yachtsman uniform circa mid1890s.

Gould became a member of the Jekyll Island Club in 1895 – the same year he donated a silver loving cup as a prize to the Golf Club of Lakewood, New Jersey, and the same year he purchased sixty acres of land for the Ocean County Hunt and Country Club, which would become a rival to the former. The founding and support of golf clubs was very much on his mind in 1895-96. Perhaps he was a factor in what may have been something of a campaign by the Club’s ardent votaries of the ancient game in 1896 to “make plain” to the Executive Committee the need for development of a golf course at Jekyll Island.

Lakewood’s village of millionaires was one of the first areas of golf’s development in New Jersey, where Dunn was invited to lay out a course in the fall of 1893. His account of the initial survey of the land for the nine-hole course of the Golf Club of Lakewood is the stuff of legend:

Robert Bage Kerr and Jasper Lynch, two well-known New Yorkers [the former became club president and then Secretary of the U.S.G.A.; the latter, the club’s golf captain], got me to look over some grounds at Lakewood, New Jersey, which they thought might be suitable for a golf course. The day we went to look over this place was rather chilly, so I wore my velvet-trimmed, gold-braided scarlet golfing jacket – no golfer’s wardrobe was complete without one in those days. However, had I known that the ground I was going to look over was being used for a cattle pasture, I certainly would have worn something more soothing to the eyes. As it was, we had just started on our tour of inspection when we were charged by an angry bull. I ripped off my jacket and threw it aside, distracting the bull’s attention so that we were able to scramble over the nearest fence. We had a good laugh over it, but my snappy jacket was a total loss. The actual construction of this course did not offer many problems. The fields were flat, so we used road scrapers and made little inclines and undulations. There were a good many trees, so that some had to be taken out, but we left as many as possible and, in the end, made a very picturesque eighteen hole course of it. (Golf Illustrated, vol xxxi no 6 [September 1934], p. 25)

This story of the origin of the course at the Golf Club of Lakewood once again shows the perils of relying on Dunn’s memory: the golf course that he designed in 1893-94 comprised not eighteen holes, but nine: it was not until 1896 that it was extended into a neighbouring field and made an eighteen-hole course.

Of course the point of the story was the bull, and there was often some “bull” in Dunn’s accounts of his exploits as a golf course architect. As we shall see shortly, at Jekyll Island he confronted an alligator: a “Crocodile” Dunn deed!

Figure 24 George Gould and caddie conferring with tournament officials (in broadbrimmed hats) while playing at the Greenwich Golf Club in Connecticut in 1897.

Gould would certainly have known of Dunn’s work in golf course design, both at the Golf Club of Lakewood and at the many other golf courses in the U.S. Northeast where Gould played golf. He would no doubt have been one of the Club members ready to recommend Dunn as the designer of the Jekyll Island Club’s first golf course.

In fact, Gould was part of a sporting cabal at Lakewood that included all sorts of men who new Dunn’s work. They played golf together, and they hunted foxes together. In 1895, for instance, the Lakewood Hunt Club comprised Arthur B. Claflin as president, Gould as vicepresident, and as Stewards both Jasper Lynch and Robert Bage Kerr – the men who along with Dunn had been chased by a bull while laying out the nine-hole golf course for the Golf Club of Lakewood in the fall of 1893.

J. Pierpont Morgan, Sr

Figure 25 J. Pierpont Morgan, Sr, in the late 1890s, then Commodore of the New York Yacht Club. He regularly sailed his yacht Corsair up the Hudson River to his home, Cragston.

Recalling that the Jekyll Island Club’s Executive Committee had been confronted sometime in 1896 with the “necessity” of providing “conveniences” for various sports for “the younger set” (golf being part of the list of “all that is desirable for the young”), we should note that J. Pierpont Morgan, Sr, was a Jekyll Islander with golf-mad children (Morning News, 11 January 1897, p. 3).

Morgan, an original member of the Jekyll Island Club, found that at least two of his children were passionate about golf: his son J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr, known as “Jack,” and his daughter Anne, six years younger than Jack. Although Jack was twenty-six and Anne was twenty, their dad did what any multi-millionaire dad would do when the new game of golf began to establish itself amongst the well-to-do classes in America in the mid-1890s: he built them a golf course.

The New York Sun wrote an article about the phenomenon of wealthy men building private golf courses, commending Morgan’s practice as one that would help to establish the game in America and help with the development of golf skills:

Golf is outstripping all the outdoor games just now in its rapid growth. It took years to fully acclimatize tennis, and, with the exception of baseball, which is a home product, the other fresh-air games and recreations have only become popular by slow degrees. But golf is advancing with seven-league strides, like Jack in the fairy tale, and will soon travel the continent over, from the Arctic line to the Mexican border, for the game is spreading through Canada as well as the United States.

One cause of the popularity of golf is the many ways the game may be taken up and because all can play at it, from the minors to the graybeards, with varying degrees of skill, of course, but with universal enjoyment. The links may be laid out on a lawn, with only two or three holes and the dirt walks or carriage drive the only hazards, or thousands of dollars may be expended on the formation of a course. In the latter case the links will be for the membership of a large club, as a rule, but some of the private courses have cost large sums and are planned on a large scale as though intended for open tournaments.

A fine practice course is laid out on the lawn of Cragston, J. Pierpont Morgan’s place on the Hudson. It consists of only a few holes, without any artificial hazards. Similar links are laid out at many country houses, and they are a good model to follow by the residents of country neighborhoods who want to take up golf. A start can be made in a small way, and when the pioneers in the game have learned to play in good form a better course can be laid out. (8 March 1896, p. 9)

So for the sake of his kids’ love of the game, a loving father turned the front lawn at Cragston into a fairway in the mid-1890s.

Figure 26 The front lawn at Cragston made a fairway, as seen in the 1930s.

At Cragston, bliss it was on that lawn to be alive. But to be young was very heaven for Jack and Anne.

Figure 27 Golf brats: J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr, known as "Jack," and Anne Tracy Morgan, circa 1900.

If Jack and Anne did not prompt their father to initiate a conversation in 1896 among Jekyll Island Club members about the need to build at least a rudimentary “Golf Ground” on the island for the younger set, we can guess that since Morgan had already built his kids a golf course on his front lawn at Cragston, he would have put his two cents’ worth into any such conversation of which he became aware.

“Jack” Pierpont Morgan would become president of the Jekyll Island Club in the 1930s and play some of the happiest rounds of his life on the Walter J. Tavis “Oceanside” course.

William Bayard Cutting, Sr.

Figure 28 William Bayard Cutting, Sr.

William Bayard Cutting, Sr, another original Jekyll Island Club member, was even more passionate about golf than Morgan –– and he had a child even more passionate about golf than Morgan’s children. His son William Bayard Cutting, Jr, was a golf prodigy. In the New York Sun’s 1895 discussion of private golf courses that “have cost large sums and are planned on as large a scale as though intended for open tournaments,” the writer singled out the course that Cutting had made for his son as the one that best represented the state of the art: “One of the best private links was laid out last season by Willie Dunn for W. Bayard Cutting on his place at Islip. The country there is very flat, and earth bunkers have been built on an extensive scale” (p. 9).