Introduction

In September of 1895, Madeline Mary Geale (1865-1923) won the ladies’ championship at the first playing of the International Golf Tournament at Niagara-on-the-Lake.

The prestige of the “International championship” in the world of North American golf in 1895 cannot be overestimated. After all, both the U.S.G.A.’s Amateur Championship and its Open Championship were delayed in 1895 in order to accommodate the Niagara tournament: “The championship golf matches, both amateur and professional, which were to have been played on the links at the Newport Golf Club early in September, have been postponed until the first week of October on account of the Canadian tournament in the second week of September” (Boston Globe, 21 August 1895, p. 7).

By his victory in the inaugural 1895 International tournament, Charles Blair Macdonald – widely regarded as the best American amateur golfer at this time (although he had been born in Niagara-on-the-Lake) – began to redeem his two surprising second-place finishes in 1894: first, at the so-called “American” amateur championship at the Newport Golf Club of Rhode Island in September of 1894, and, second, at the so-called “United States” amateur championship at the St Andrews Golf Club of Yonkers, New York, in October of 1894.

Figure 1 Charles Blair MacDonald (1855- 1939), circa 1895.

Chicago newspapers saluted his Niagara win in no uncertain terms: one said, “Chicago claims the champion golf player of the continent. Charles B. Macdonald, president of the Chicago Golf Club, won the international championship”; another said the same thing slightly differently: “Charles B. MacDonald of Chicago tonight bears the proud title of champion golf player of the United States and Canada” (Inter Ocean [Chicago], 9 September 1895, p. 3; Chicago Chronicle, 8 September 1895, p. 4). When MacDonald won the 1895 U.S.G.A. amateur championship a few weeks later at Newport, Rhode Island, the same newspaper ranked MacDonald’s win at the International Championship as equal to the amateur championship: “Charles Blair MacDonald, amateur champion of the United States and international champion, …. now holds the only two championships worth striving for” (Inter Ocean, 4 October 1895, p. 4).

Figure 2 Madeline (sometimes spelled "Madeleine") Mary Geale (1864-1923), Niagara-on-the-Lake, circa 1895.

As the first USGA national amateur championship for women would not be held until November of 1895, and as the RCGA would not hold a national amateur championship for women until 1901, Madeline Geale held the first and only North American championship for women up to that point. Like MacDonald, she became the champion golf player of the continent, bearer of the proud title of champion golf player of the United States and Canada.

Note also that even if one were inclined to claim that MacDonald was technically a Canadian because he had been born in Niagara-on-the-Lake, since the women’s championship match was played in the morning on the final day of the tournament, whereas the men’s championship match was played in the afternoon, Geale remains nonetheless the first Canadian to win an international golf championship.

And so, Madeleine Mary Geale holds a unique place in Canadian golf history. Her story should be told.

A Renaissance Woman

When it came to golf, Madeline Geale was many things.

In addition to being Canada’s best woman player, she wrote fiction and poetry about golf, she was the secretary-treasurer of the Niagara Golf Club (apparently the first woman in North America elected to the executive committee of a golf club), she named the holes of the new nine-hole layout on the Fort George Common in June of 1896 (along with club founder Charles Hunter, who insisted that the fifteenth hole on the course be named after her, “Geale’s”), and she probably helped Hunter and her cousin John Geale Dickson lay out this course.

She also wrote essays, fiction, and poetry about many topics besides golf. In the Canadian Home Journal in 1897, for instance, we find “a very graphically written sketch of a trip from Toronto to Chippawa from the pen of Madeleine Geale” (Ottawa Citizen, 22 September 1897, p. 6; Canadian Home Journal, vol 3 no 5 [September 1897]). Her short story “The Pantry Ghost” in the Canadian Home Journal the next year was said to be “well worthy of perusal” (Lethbridge News, 4 May 1898, p. 8; Canadian Home Journal, vol 4 no 1 [May 1898]). Under her married name (Windeyer), she published the poems “Love’s Awakening” and “Drifted” in Ainslee’s Magazine (in July of 1903 and February of 1904, respectively) and the poem “In Memoriam” in Munsey’s Magazine (May 1910). A short story called “Sandy’s Old Woman,” accompanied by professional illustrations, appeared in Everybody’s Magazine (December 1904).

Figure 3 Madeleine Windeyer, "Sandy's Old Woman," Everybody's Magazine, vol 9 no 6 (December 1904), p. 733.

And in January of 1913, a musical composition called “A Miniature” – “words by Madeleine Windeyer, music by J.D. Freeman” – was officially copyrighted (Catalog of Copyright Entries, 1913 Compositions, part 3, new series, vol 8 no 1 [1913], p. 1266).

And there were many more poems and short stories – a good number of them about golf – which will be discussed in sections below.

Golf was not Geale’s only sport. She played tennis competitively, for instance, making it to the semifinals for tournament novices at the Canadian international tennis tournament at Niagara-on-the-Lake in the summer of 1894. The next year, she reached the finals.

In 1896, Toronto’s Globe newspaper reported the Niagara Golf Club’s opinion that Geale “is a lady of great executive ability and business capacity” (The Globe [Toronto], 19 June 1896, p. 10).

Geale seems to have given up competitive golf around the time of her marriage in 1899. She gave birth to her one and only child in 1900. And after that, in her spare time as wife, mother, poet, and writer of fiction, she raised money for the Red Cross Society during World War I, served as first vice-president of the 234th Battalion Auxiliary during that war, and she became a competitive yachtswoman in sailing matches on Lake Ontario.

An Old Family

Madeline Mary Geale (pronounced “Gale”) was born into a family long-resident in Canada, the United States, and the British North American colonies. The various families from which she descended had been in North America since the early 1700s. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Saturday Night magazine said of Madeline and her siblings that they were “connected with a number of the old and well-known families in society” (25 December 1909, p. 18).

And her family had long been associated with the Niagara area in particular. Her paternal grandfather, Lieutenant Bernard Geale, fought in the War of 1812, in which he was wounded and taken prisoner near Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Figure 4 Colonel William Claus (1765-1826)

Her paternal grandmother, Catherine Claus (circa 1796-1873), who had married Bernard Geale, was the daughter of Colonel William Claus (1765- 1826), who also fought in the War of 1812. He served as a member of the Executive Council of Upper Canada, and he was “for thirty years deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs in Upper Canada” (Ottawa Citizen, 2 August 1899, p. 5).

William Claus’s father had served in a similar position, having been appointed deputy to his father-in-law (Madeline Geale’s great-greatgrandfather), Sir William Johnson (1715-1774), who had been appointed the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1756 for all of Britain’s northern colonies.

Johnson had learned the Mohawk language in the 1740s and become a key figure in relations with the Iroquois people

Figure 5 Sir William Johnson (circa 1715-1774).

Johnson commanded Iroquois and colonial militia forces in the “French and Indian War” (conflicts from 1754 to 1763 between British colonists and their indigenous allies, on the one hand, and French colonists and their indigenous allies, on the other). He particularly “distinguished himself at the capture of Fort Niagara from the French in 1759” (Ottawa Citizen, 2 August 1899, p. 5).

At Niagara-on-the-Lake in 1847, Madeline Geale’s father, Captain John Bernard Geale (1819-1899), married her mother, Caroline Cox (1825-1886), herself the daughter of a captain in the British Army.

Figure 6 Left: Captain John B. Geale (1819-99), circa mid-1890s; right: Caroline (Cox) Geale (1825-1886), undated.

Madeline was the last-born child of the four boys and three girls that her parents had.

Her father had a long and distinguished military career: he “served on the frontier in the suppression of the rebellion of 1837. In 1853, he received a commission in the Royal Canadian Rifles and was appointed barrack-master at Hamilton, and subsequently transferred to Niagara as keeper of military properties, which position he held until the time of his death” (Gazette [Montreal], 19 August 1899, p. 4).

Captain Geale’s role as keeper of military properties in Niagara-on-the-Lake was probably instrumental in the plans of his nephew: Lieutenant John Geale Dickson. With his uncle’s permission, the latter laid out several golf holes on the Fort George Common in the mid-1870s, and then, along with his friend Charles Hunter, he laid out a nine-hole course on the Fort Mississauga Common around 1877 (although the greens of the original layout have been moved and re-developed since 1877, many of the original fairways remain in play today on the golf course of the Niagara-on-the-Lake Golf Club).

The Dad-Blamed Parent

Madeline’s father must have been a source of great pride and great upset for her.

On the one hand, Captain John B. Geale was respected by many.

Figure 7 Captain John B. Geale, circa mid-1890s, holding his cane.

In his reminiscences of nineteenth-century Niagara-on-the-Lake, Joseph E. Masters recalled that Captain Geale was “A fine looking man, tall and erect, sporting a moustache and side whiskers,”and that he dressed fashionably: “He carried a cane … and in winter he wore a red sash about his waist. This was quite common wear for the smart men in those days” (Joseph E. Masters, “The Masters Papers,” Niagara Historical Society Research Room, p. 289).

Masters notes that “The Captain seems to have been a publicly minded man, as he served six years in Town Council” (“The Masters Papers,” p. 422). This seems to have been in the 1860s, around the time that Madeline was born. He also ran in the Ontario provincial election of 1868, seeking to become the MLA for Niagara town and township.

He lost in a landslide, having represented the interests of the railroad companies – whose candidates were swept out of power in the Niagara area at that time at both the provincial and municipal levels.

In 1895, Captain Geale was honored for his long military service, being called upon to raise the flag over Fort Mississauga to mark the opening of that year’s summer training camp: “The flag was hoisted by the hands of Captain Geale, a splendidly preserved veteran of the old Royal Canadian Rifles” (The Globe [Toronto], 25 May 1895, p. 9).

He will have told Madeline of the outbreak of war in Crimea in 1854 and of his desire to fight for Queen and country. But, as he explained to others, “his wife wouldn’t consent to his going” (Joseph E. Masters, p. 559). And he will have told Madeline of witnessing colourful incidents in his grandfather’s life as “Indian Agent”:

Captain Geale used to tell of his remembrance as a boy of meetings at the ‘Wilderness,’ [a five-acre property at Niagara-on-the-Lake] belonging to his grandfather, Colonel William Claus …. He had seen the spacious ground around the house full of Indians who had come for their presents [i.e., monies owed by treaty] received annually. (Janet Carnochan, History of Niagara [Toronto: William Briggs, 1914], pp. 197-98).

To a little girl raised on stories of her father’s army life and of his childhood adventures, Captain Geale will have seemed a romantic figure.

On the other hand, a soldier who had served under Captain Geale in Niagara-on-the-Lake at the outbreak of the Crimean War saw Geale’s inability to serve Queen and country differently: he called him “That … Bloody Coward” (Masters, p. 559). Would the young Madeline have heard such opinions of her father voiced in the community?

In 1886, when Madeline was twenty-two years old, her mother died, and sometime after that, her father quarrelled with his family and began a downward spiral toward ruin. According to Masters,

The Captain, in his later days, was caretaker of the Government Buildings and became estranged from his family. He made the headquarters building [of the army barracks] his abode. It was during his caretakership that the extra roof was imposed on the building in Fort Mississauga. The gallant Captain fell on evil days in his old age, estranged from his family and impoverished. I had the duty, as Bailiff, of serving papers on him for debt and much of his furniture was sold by the Town for arrears of Taxes. (The Masters Papers, p. 289)

Soldier, singer, fashionable gentleman, husband, father, Town Councillor, Canadian Militia property manager, family exile, debtor …. Madeline’s father was a man with a complicated public and personal history.

How will his decline have affected her?

Captain Geale died in poverty a month before Madeline’s wedding.

Life to the Mid-1890s

Madeline’s life in her late teens and early twenties was typical of the life of the young middle-class woman of that day.

Figure 8 Part of 5.5-acre Geale's Grove (alias, "The Wilderness") circa 2019, of which four acres remain heavily wooded.

The local Anglican church, St. Mark’s, was important to the spiritual life of the family, and all three of the daughters of John and Caroline Geale taught Sunday school there, organizing church picnics in Geale’s Grove (approximately 5.5 acres of land in Niagara-on-the-Lake known since the beginning of the twentieth century as “The Wilderness”), a property granted to their great-grandmother in recognition of her husband’s (Daniel Claus’s) acts of kindness towards indigenous peoples.

Madeline was a regular participant in the usual social events involving middle-class young women. We regularly find Madeline and her unmarried sisters, for instance, mentioned as “the Misses Geale” who were invited to “a delightful little afternoon tea” here and there at the homes of the social matrons of Niagara-on-the-Lake (Buffalo Commercial, 6 July 1895, p. 7). A young woman might be invited to enliven one of these events with performance of a song, the playing of a musical instrument, or the recitation of verse or drama. As a published author, and therefore something of a local celebrity, Madeline Geale would regularly have been called upon for contributions of this sort.

In her mid-twenties, she clearly enjoyed the company of children, delighting in entertaining them. For instance, she helped out at the big “party at the Anchorage given in honor of the twelfth anniversary of Master Joey Syer’s birthday,” where she supervised “dancing and games of every description,” helped to seat “the merry little guests” at “little tables” where “ices and delicacies of every description” were served, and so was acknowledged as one of “the older ones who helped to amuse the children and who seemed to enjoy the games as thoroughly as the juveniles” (Saturday Night [Toronto], 12 September 1891, p. 11).

And in her mid-thirties, she still delighted in entertaining children. At “the annual Festival held in the Park … under the management of the Guild of St. Mark’s” in the summer of 1895, she presided over the most popular of “the prettily decorated booths … bright with Chinese lanterns”:

One half of the tent [housing the “fancy table in white and crimson”] was claimed by Miss Arnold and Miss M. Geale, who managed a mysterious thing under the name of a Cherry Pie, out of which came parcels of all sizes and shapes. This, of course, was generously patronized by the children, who immensely enjoyed the glorious uncertainty attached to a dip under the cherry-colored netting. (The Buffalo Commercial, 27 June 1896, p. 14).

It seems that Madeleine Geale’s creative bent was not just confined to her writing.

And her writing occasionally concentrated on children’s topics, such as “Dorothy’s Dream” (1909), an enchanting poem about a young child’s dream of encounters with elves, fairies, and brownies in a garden where flowers smile and laugh, and crickets dance. The opening stanzas run as follows:

When all the world was hushed last night,

I saw a very funny sight.

I dreamt that I was standing still

Just underneath my window sill,

With daisies all around my feet,

And grasses cool and wild and sweet.

And all about the cottage wall

Were bobbing weeds and flowers tall,

And little things with golden leaves

Like webs a fairy spider weaves,

And swarms of little elfish things

With fluffy feet and silver wings.

I held my dolly very tight

And wondered at the funny sight,

For round and round and in and out

The queerest Brownies danced about,

And every one that stood around

Played dummy harps that would not sound.

And over on a patch of green

Two bunnies sat and watched the scene,

While fairies fled with wings outspread

Before the Brownies’ lightsome tread.

The moon looked down with face aglow

To see how fast their feet would go –

Such little feet, so small and round,

They hardly seemed to touch the ground.

And all the stars with twinkling eyes

Laughed merrily and thought them wise,

And called them strange and queer and grand,

The Brownies and the fairy band.

(Cassell’s Little Folks [London, New York, Toronto: Cassell and Co., 1909], p. 64)

This poem was written when her own child was nine years old, and so one might speculate that it had been written for him.

Military Society

Given her family’s military background, it is not surprising to find Madeline Geale socializing within the military community, especially since her father continued to serve in the Canadian Militia and “was extremely popular” in “a very large circle of friends” (Gazette [Montreal], 19 August 1899, p. 4). Joseph E. Masters says that he was “a fine-lookingman, wearing a moustache and side whiskers, and that “he had a fine singing voice” (“it was a treat to hear him”) (“The Masters Papers,” p. 233). Francis MacKay, of the Niagara Historical Society, concurs: “J.B. Geale was noted for his dashing charms and fine singing voice which contributed much to the choir of St Mark’s [Anglican Church] as well as soirées” (https://www.niagaraonthelakeinn.ca/history/lyons-house-historical-notes/).

And so, in 1890, we find Madeline Geale alongside the best of Niagara-on-the-Lake high society watching a mock battle played out by the local militia forces across the site of the Fort George Common where Geale would six years later help to lay out the Niagara Golf Club’s new eighteen-hole course in June of 1896.

The woman who was in the summer of 1896 the reigning champion woman golfer of North America and the secretary-treasurer of the Niagara Golf Club, preparing a new layout to host huge crowds excited to watch the international golf skirmishes of red-coated players from Canada and the United States, was the woman who in the summer of 1890 was listed among the “fair ones” that Saturday Night Magazine named as observers of the military exercise that marked the end of that summer’s training camp for certain units of the Canadian Militia:

A great number … came on Friday for the sham battle, which brought the twelve days’ camp to a close. Early in the afternoon, crowds gathered from every direction and thronged the ramparts of old Fort George, from which a splendid view of the field could be obtained. Although the heat during the first part of the afternoon brought a rather unbecomingly deep flush to many an otherwise bewitching face, few found it too warm to remain for the exciting and splendid manoeuvres which later delighted the large crowd of spectators. The excitement of some of the ladies became slightly alarming, and once a few feeble screams relieved the feelings of the more timid when a line of red-coated skirmishers unexpectedly charged up the side of the fort embankment, but the smiling faces of the invading party were so reassuring that the fears of the fair ones were soon lost in the intense interest with which they watched the advance of pursuers and the retreat of the routed enemy. (Saturday Night [Toronto], 5 July 1890, p. 11).

She also attended the end-of-summer balls that marked the conclusion of the training camps at Niagara-on-the-Lake for the local militia companies, including those from Toronto.

In the summer of 1895, Madeline Geale was among prominent Niagara-on-the-Lake residents invited by the American troops to visit Fort Niagara:

Never before have the officers of the Niagara Brigade Camp and the blue coats from Fort Niagara exchanged such unusual and marked civilities – socially – as during the last ten days.

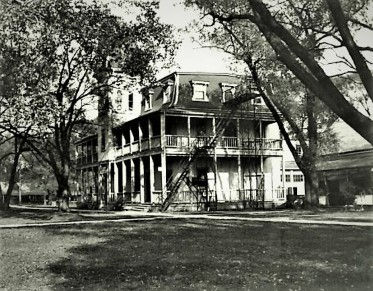

Figure 9 Fort Niagara, Youngstown, New York, late 1890s, as seen when approaching by boat from the Canadian side of the Niagara River at Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Dinners and dances have followed fast upon each other on both sides of the water, but the dances given by the officers of the 13th U.S. Regiment in honor of the Canadian Red Coats outshone them all. It was in every way a thoroughly charming and most enjoyable affair …. The guests from across the river were met at the landing by a guard of trim privates, who escorted them to the adjutant’s office … and from there to the gaily decorated ball room …. The floor, the supper, the music, everything was perfect, and although boats and cabs had been ordered for twelve, it was not until after two that the soft strains of Auf Wiedersehn – the last waltz – floated out over the river, followed by Auld Land Syne, and God Save the Queen. Even then everyone seemed reluctant to go. (Buffalo Commercial, 29 June 1895, p. 5)

Only a relatively small number of the many dozens of American and Canadian guests who attended the event were named in the newspaper, but one of them was “Miss Madeline Geale” (Buffalo Commercial, 29 June 1895, p. 5).

Her Poetry in General

Dramatic recitation of poetry was a regular feature of women’s social events. Writing poetry oneself was also fairly common, but writing it competently and publishing it was much rarer.

Most of Geale’s poetry is relatively conventional and quite competent regarding rhythm and rhyme, as we can see from the opening stanzas of “Dorothy’s Dream” cited above.

The themes and style of two of her best poems make clear that she has studied closely the great British poets of the nineteenth century. For instance, in “Winter at Niagara-on-the-Lake” (1894), she implicitly recalls “Dover Beach,” the celebrated poem of her great Victorian precursor Matthew Arnold, who combines the image of “the grating roar / Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling” upon the shore with the image of human beings “on a darkling plain / Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, / Where ignorant armies clash by night”:

Winter at Niagara-on-the-Lake

No tumult here,

No ceaseless tramp of hurrying toilers’ feet –

Only a hush above the wide old street;

Or loud and clear,

Up from the long, low line that bounds the lake,

The noisy crash of waves that rise and break.

And over all,

Lost in the hush and mingling with the roar

Of sullen waters breaking on the shore,

The bugle call

Drifts from the Fort, that nestles, quaint and low,

Beyond the river’s frozen fields of snow.

(The Canadian Magazine of Politics, Science, Art, and Literature, vol 2 no 5 [March 1894], p. 428)

This poem was republished in the Buffalo Morning Express in 1897 (17 January 1897, p. 2).

In an 1896 poem (written at the time she created the popular “cherry pie” device for children at the St. Mark’s summer Festival), Geale takes Romantic poets William Blake (1757-1827) and William Wordsworth (1770-1850) as her models for a poem about a child. In the two-stanza poem called “Two Answers,”Geale introduces a person speaking to a little child. In the first stanza, the adult tells the child she lovers her, and the child immediately responds in kind. In the second stanza, however, the little girl has grown old enough to be called “a maid,” and so, when the adult tells her again that she loves her, the older child no longer responds in kind:

Two Answers

“I love you, sweet,”

I said to a child,

Whose curls in a mass of tangles wild

Fell over the shoulders, soft and fair,

Kissed by the sun and the summer air.

“I love you, sweet”;

And she turned and smiled,

The frank, fresh smile of a trusting child.

“I love you, too;

“I love you best,”

The lips of the little one confessed.

“I love you, sweet,”

I said to a maid,

And the dimples alternately went and stayed.

“I love you, sweet”; and the laughing eyes,

Blue as the bluest summer skies,

Looked shyly up,

And as shyly down

Under the lashes of golden brown;

But I waited in vain for the words confessed –

“I love you, too;

I love you best.”

(The Argosy, vol 42 no 4 [July 1903], p. 699)

The second answer provided by “the maid” – silence – speaks the meaning of the poem. Madeline Geale follows the tradition of Blake and Wordsworth, who regularly reflect on how the experience that children acquire as they grow up slowly deprives them of the innocence and trust with which they enter the world, gradually making them more guarded about what they will confess to others.

This 1896 poem became a favorite of editors, reappearing several times over the years, including republication in The Argosy magazine in 1903 and in the Morning Register newspaper of Eugene, Oregon, in 1904.

Her Short Stories in General

The short story form had become popular by the late 1800s and early 1900s. As opposed to long Victorian novels full of many characters and many storylines, the short story generally focussed on a couple of characters and a single event in a moment of time. And the plot typically produced a surprise at the ending of the story.

Geale’s story “Sandy’s Old Woman” exemplifies these short-story traits.

Geale tells of an impoverished boy named Sandy who received from a woman who nursed him through illness a book called Legends and Folktales, one of the stories telling of how a certain grand house contains gold for those who can enter it and find the right room at dawn on Christmas Eve. Mistaking the book for an account of the real world, Sandy enlists his even poorer friend Curly to search their town for the mysterious house described in the book. Finding a grand one that approximates the house in question, Sandy sends Curly in.

Figure 10 Madeline Windeyer, "Sandy's Old Woman, illustrated by B. Cory Kilvert, Everybody's Magazine, vol 11 no 6 (December 1904), p. 737.

Apprehended by the household servants and set before the homeowner in the middle of the family’s Christmas party, Curly cannot find words to respond to the interrogation that follows, so he pulls Legends and Folktales from his pocket and points to the relevant page. The homeowner reads it aloud, he and his guests dissolve in laughter, and they soon resolve to fulfil the boy’s expectations. He is given a sack full turkeys, plum puddings, and mince pies, and added to it are gifts from under the Christmas tree. Curly is then told to open a desk drawer and to add to his sack a handful of the coins he finds there.

Sent on his way, Curly rejoins Sandy, and, in wonder and triumph, they inspect their treasure.

Her brief short story “Fore!” (published in Saturday Night in 1902) is similar.

Fore!

Two people, one young and fresh, with soft, windblown hair, and the brown roses of the sun glowing through the pink and white of her dimpled cheeks. And the other a little old maid, with the shadow of a disappointed life in her faded eyes.

“Golf! Golf!” she said bitterly, as she lifted the clubs the girl had laid on the table, and deliberately dropped them out of the window. “Never let me hear the word, child, never bring those terrible sticks into my house. Many times, long ago, I heard that golf was a game in which men cheated as often as they chose and no one could prove otherwise. They told me nine out of ten played it unfairly, that no one ever knew if the other could be trusted, that even the little boys who carried the sticks were bribed. Fences and hollows and hills hid the players from each other and left them free to do as they wished. I did not believe them. I loved someone who loved the game, and one day I went up the course with many others. They went to see the game. I went to watch the players.”

She paused, forgetting the other, who had grown strangely interested. “Well?” asked the girl at last.

The little old maid woke with a start from her dreaming, and her grey curls bobbed excitedly as she went on. “Yes, it was true. I had thought him so immeasurably above anything petty or mean – and I saw him cheat. I heard him lie to win a game. I did not pretend to understand how they played, or how many shots were necessary to win or lose, but I could count. That was enough.”

Again she paused, and again the girl’s enquiring “Well?” urged her on.

“Yes, I counted, to my sorrow. He put his ball on a little lump of mud and knocked it off, and I jotted down ‘one.’ Five times he hit it between that and a certain field. Then his ball went down into a pit that came in his way, and remembering what they said about cheating, and smiling to myself in my absolute confidence in him, I watched. Ah! He disappeared from sight, and just as I said to myself, ‘He is playing his seventh,’ he called at the top of his voice: ‘Four!’”

“My head swam. I could hardly believe my senses. Four! When I had counted every shot and knew it was seven! I held my breath, thinking surely he would remember and correct his mistake, but instead he called again, loudly and defiantly: ‘Four!’”

“Child, that was forty years ago, and I have never seen him since. You may think it was a little thing, but if he would cheat in a game, for nothing but the winning of a day’s sport, how could I trust him in anything? It was the bitterness of my disappointment in him that killed the love. To cheat, with a falsehood added, and for such a little thing, for such a little thing!”

“And didn’t you ask him? Didn’t he explain?”

“ – Ask him? Explain! No. I told him nothing. I asked nothing. One falsehood more would not have bettered things. They told me afterwards that he won the match by a shot, and I knew that the honor and the trophy he carried away were stolen things. How could he have explained?”

The girl rose to her feet with a torrent of words on her lips. They died away unuttered as her eyes fell on the grey curls, the worn cheeks, the faded eyes, and she remembered the stretch of years between. “Oh! The pity of it, the pity of it,” she said to herself, as she stole softly away.

M. Geale Windeyer (Saturday Night [Toronto], 8 February 1902, p. 7)

The two stories are similar. The “little old maid” lives out a delusion that both the reader and the young girl in the story recognize. The young boys live out a delusion that both the reader and the people in the story recognize. And the author makes us ask ourselves whether or not it would be better to apprise the old woman and the young boys of their delusions or to leave them be.

Early Golf

Just when Madeline Geale first took up golf is not clear.

The Buffalo Morning Express claimed that 1895 was “her first season’s playing” (25 July 1896, p. 7). The Inter Ocean newspaper of Chicago, however, asserted that by 1895 Geale was “conversant with every nook and corner of the [Niagara] links, having played on them daily for the past three years” (9 September 1895, p. 3).

Perhaps the information in the two newspapers can be reconciled: it may be that the Buffalo newspaper means that 1895 was her first season of competitive tournament play, and it may be that the Chicago newspaper means that she had been playing golf socially at the Niagara Golf Club for several years before the 1895 season.

Interestingly, when Geale was elected secretary-treasurer of the Niagara Golf Club in the spring of 1896, it was noted that she “has always taken the greatest interest in golf at Niagara” (The Globe [Toronto], 19 June 1896, p. 10, emphasis added). The word “always” would not have been appropriate in this commendation if Geale had been involved with the club only since the beginning of the 1895 season twelve months before this statement was made.

What is interconvertible is that when Madeline Geale took up the game, she became obsessed with it: she played the game daily. Following her victory in the inaugural International Golf Tournament, she was interviewed by the Buffalo Morning Express about her experience of golf:

A prominent member of this [Niagara-on-the-Lake] coterie of enthusiasts is Miss Madeline Geale, who is the champion woman golf player of Canada, having won her laurels last year in her first season’s playing. She confesses that before she played herself, she thought it frightfully stupid to chase balls all over a hot, sunny field, but now she would rather play than eat. (Buffalo Morning Express, 25 July 1896, p. 7)

Those of us who are addicted to golf know whereof Geale spoke in 1896.

And after her conversion to golf, she had little tolerance for women who affected to play golf but were really playing a different game:

Two Kinds

A sight for the gods, indeed!

A blouse of blue, and a skirt of tweed,

A glimpse of an ankle, trim and neat,

And stout, spiked shoes on the shapely feet,

A dimpled face, sun-browned and fair,

And a gleam of gold in the wind-blown hair.

And with her another strode,

While a caddie shouldered her shining load.

She wore a hat that was Fashon’s pride,

With puffs in front and plumes at the side.

Her waist was pulled into slender grace,

And a veil protected her tender face.

In fact, her style was a duplicate

Of a stunning cut in a modiste’s plate.

Ghost of a golfer! Fancy that,

High-heeled shoes, and a picture hat!

Gloves on her hands and a train to her gown.

And ivory cheeks instead of brown!

And yet, by thunder! There are such girls

Who golf in ribbons and borrowed curls,

Who haunt the links when the days are fair

Because of the fellows and fashion there,

While down in their hearts, misguided dames,

They’ve not but scorn for the game of games.

Away, all such, to your gentle sports,

Hie off to your teas and your tennis courts;

God’s fields, and downs, and sun-lit hills

Are not for the women of fads and frills.

The winds blow sweet, and the skies are blue,

But the breath of the links is not for you.

(Saturday Night [Toronto], 27 April 1901, p. 7)

Geale uses the trusted rhyming couplet of eighteenth-century poets such as Alexander Pope to mock her target: women who use golf to display themselves before eligible bachelors.

“Two Kinds”was republished in 1902 in Britain’s premier golf magazine, Golf Illustrated (vol 11 no 34 [3 January 1902], p. 14).

Niagara Golfing Forebears

Whenever it was that Madeline Geale decided it was not “stupid to chase balls all over a hot, sunny field,” her aptitude for the game will have immediately been noticed by the club’s best players: her much older cousins, John Geale Dickson and Robert George Dickson, and a summer resident of Niagaraon-the-Lake name Charles Hunter who became an admirer of her golf game and her golf mentor in general.

Figure 11 John Geale Dickson. Canadian Golfer, vol 16 no 9 (January 1931), p. 677.

Madeline was the first cousin of John Geale Dickson (1845-1931), who first laid out three holes on the Fort George Common in the early 1870s:

Educated at Galt and Cobourg, Mr. Dickson and his twin brother, afterwards Captain [Robert] [George] Dickson, went to England, where they entered the army.

It was while an officer [lieutenant] in the 47th Regiment in 1871 … that Mr. J.G. Dickson took his first lessons in golf.

Leaving his regiment in 1872 and returning to Niagara, his birthplace, he settled there and with Mr. Ingersoll Merritt, late of the 30th regiment, laid out a rough links on the Southeastern [Fort George] Common or Government Reserve there. (Canadian Golfer, vol 16 no 9 [January 1931], p. 677.

John Geale Dickson was twenty years older than his cousin Madeline. When Dickson set up the first golf course in Niagara-on-the-Lake, she was less than ten years old.

Subsequently, with Charles Hunter(1847-1922), who lived in Toronto (where he was chief agent for the Standard Life Assurance Company) but maintained a summer home in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Dickson laid out a nine-hole course around Fort Mississauga around 1877.

Hunter was perhaps the most influential member of the Niagara Golf Club. As Janet Carnochan observes, “In 1877, the club was organized chiefly by the exertions of Mr. Charles Hunter, who ever since has been its strongest supporter” (History of Niagara, [Toronto: W. Briggs, 1914], p. 260). This club lapsed after a few years, but the Niagara Golf Club was re-formed for good in 1881. Hunter served on its executive committee perpetually (often as president), was instrumental in organizing in 1895 its famous International Golf Tournament (which endured for twenty years), and religiously documented its history in a scrapbook now in possession of the Niagara Historical Society.

He was a good friend of Madeline Geale’s: he invited her to serve alongside him on the committee organizing the International Golf Tournament of 1896; they went out together on the new St. George links of 1896 and named the holes together; and she gave him an autographed photograph of her for his scrapbook.

It is possible that Madeline Geale is the unidentified woman in the photograph below that shows Charles Hunter and his wife, Emily Joanna Lauder (a St Catherines’ woman that he married in 1878), on the Niagara-on-the-Lake golf course in the late 1880s or early 1890s.

Figure 12 Three caddies and three golfers on the Niagara-on-the-Lake golf course. Left: Charles Hunter. Right: Mrs. Charles Hunter (Emily Joanna Lauder). Middle: unidentified woman (perhaps Madeline Geale). Richard D. Merritt, On Common Ground (Toronto: Dundurn, 2012), p. 195.

Robert Geale Dickson (John’s twin brother) became the first captain of the Niagara Golf Club when it was formed in 1881.

Figure 13 Captain Robert George Dickson (1845-1924), circa early 1870s.

Robert Dickson, John Dickson, and Charles Hunter are remembered today as among Canada’s golf pioneers.

In the early 1880s, they organized Niagara Golf Club matches against the only other golf clubs in Ontario at the time: the Toronto Golf Club and the Brantford Golf Club. They also represented Ontario in interprovincial matches with Quebec, and they arranged for the Niagara Golf Club to host the interprovincial match of 1883.

Although Madeline Geale initially looked askance at the game, she must have had many occasions to observe it up close in Niagara-on-the-Lake, and not just because her cousins were so enamoured of it, for golf matches in the 1880s were exotic events – attracting curious spectators, interested to see both the unfamiliar game (with its odd implements and peculiar swing) and the bright red coats that the golfers wore in those days (contrasting so dramatically with the green field over which they strode so purposefully).

Miss Geale's Playground: the Mississauga Links

Eight women entered the International Tournament of 1895 from golf clubs in Quebec, Ontario, and the United States. All were eager to test themselves in the first great golf championship for women to be organized in either Canada or the United States. Although the championship “was not the result of a deliberate act on the part of the two Associations,” the “International Amateur Golf Tournament, held at Niagara-on-the-Lake in September, had … the tacit sanction of the United States and Canadian Golf Associations” (The Golfer, vol 2 no 1 [November 1895], p. 7).

The men’s tournament was by match-play over eighteen holes. The first nine holes were played on the nine-hole Fort Mississauga Links, and the second nine holes were played on the new Fort George Links, to which the competitors were taken by a carriage ride across town. The women’s championship, however, was by medal play over just nine holes, which were played on the Fort Mississauga Links.

Tournament organizers laid out the new nine holes of the Fort George links over the summer of 1895, but they were at work on significant improvements to the Fort Mississauga links even earlier that year:

The golf course, starting from the grounds of the Queen’s Royal Hotel, laid out over as fine a stretch of common as can be seen anywhere, consists of nine holes and is one and a half miles [i.e., about 2,640 yards] in extent. The hazards consist of a series of broken ground about Fort Mississauga, rifle pits, old fortifications, embankments, moats, wet and dry ditches, water, and sandy shore. Many of the holes are of extremely sporting character and sufficient to bring even the most experienced players to grief. Great improvements are to be made on this ground in the spring and it is the intention of the committee to form a golfing green worthy of the surroundings. (The Times [Niagara-on-the-Lake], 4 April 1895, p. 8)

The condition of the golf course on the Fort George Common was not all that the Niagara Golf Club had hoped it would be by September, for it had been rushed to completion so that the men’s championship at the International Tournament could be conducted on a proper eighteen-hole golf course. A reporter for the Chicago Times-Herald observed: “The fact of the matter is that the greens are by no means in first class order. Putting greens are not made in a day – particularly in ‘clayey’ soil, which demands a good deal of treatment to make a proper course” (cited in Kansas City Star, 11 September 1895, p. 4).

But conditions on the long-established Fort Mississauga links were far worse. The problem was cows: “cattle have been permitted to roam at will over the course, and that alone is sufficient to place the links out of the order of the first class” (Chicago Times-Herald, cited in Kansas City Star, 11 September 1895, p. 4).

Cattle had grazed on the common right up to the day before the first matches were played:

Early in the afternoon, a drove of over 100 cows passed over the St. George links [this is an error: the cows were on the Fort Mississauga – not the Fort George – links] and one feminine golfer – properly a “golferine” – tried a long and elevating drive from the tee over the passing cows and much to her own and everybody’s surprise landed the gutta-percha ball in the midst of the cows. One cow thought that it was a delicatessen of some sort, dropped from some place for her sole benefit, for she tried to eat it. But the attempt was unsatisfactory, and the animal turned from it with disgust. The young woman considered it an extreme hazard to venture among the cows to recover the ball, but a caddy was more venturesome. (Buffalo Courier, 7 September 1895, p. 6)

Farmers had been using the Mississauga Common as a grazing ground for their cattle from a time before the golf course was laid out on it. The image below, from a historical plaque at Fort Mississauga, shows cattle grazing in the moat around the fort around 1879, a year or two after John Geale Dickson and Charles Hunter laid out the first course on the Mississauga Common.

Figure 14 "Old Fort Mississauga circa 1879," Historical Plaque, fort Mississauga, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario.

An anonymous American competitor was interviewed by an American reporter about the problem caused by the cattle (this person may have been C.B. MacDonald, who is quoted by name in the article a few lines later offering his assessment of the Canadian players), and the player complimented the tournament organizers for having done their best: “The men of Niagara … have done all that they could under the circumstances to put the ground in good condition, and I must say that few courses have an historic old fort for a hazard. The ground forms a pleasing view to the to the artistic eye of the novice, but when a golfer looks at it, he sees at once its shortcoming” (Buffalo Courier, 6 September 1895, p. 6)

So many complaints arose about the effect of the cows on the golf course that within weeks of the conclusion of the tournament, the Niagara Golf Club began to consider laying out an 18-hole course entirely on the Fort George Common southeast of the town. As the editor of the Boston journal The Golfer observed:

The links at present are certainly not in good condition, but the soil to the south of the town on the Niagara River is excellent and, with a reasonable amount of money expended, there can be made a fine golfing course. The ground is owned by the Dominion Government and steps are being taken to secure control of the common so that the course can be properly laid out and improved without fear of being ruined by the grazing of cattle. (The Golfer, vol 2 no 1 [November 1895], p. 7)

Located at one end of the Fort Mississauga links was the pavilion of the tournament sponsor, the Queen’s Royal Hotel (which had first broached to Canadian clubs the idea of a grand tournament in Niagara-on-the-Lake in the spring of 1893). At the opposite end of the course was the summer residence of Charles Hunter.

The sketch below, from the Buffalo Courier in the summer of 1895, shows the view across the Fort Mississauga golf course (which was also called the “Lakeside Links”), looking towards the Queen’s Royal Hotel (seen in the far background on the extreme right side of the sketch) from the part of the golf course located in front of the summer home of Charles Hunter.

Figure 15 Buffalo Courier, 18 August 1895, p.9.

Fort Mississauga is seen in the centre of the sketch. Lake Ontario is on the left, the ferry from Toronto arriving at Niagara-on-the-Lake. A golfer putts on what is probably the third green of the 1895 course, to which he has played from a tee located on top of the embankment around Fort Mississauga. The second green and the sixth green were located on opposite sides of the fort seen above, laid out on the flat bottom of the dried-up moat seen in the postcard image below.

Figure 16 Postcard showing Fort Mississauga circa 1900.

The Canadian Militia used the Mississauga Common for exercises in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Figure 17 Bell tents of the Canadian Militia pitched around Fort Mississauga circa 1900.

The Militia conducted mock battles on the common in which mounted cavalry charged across the golf course and artillery carriages were drawn across it, so grazing cattle were not the only source of unusual hazards for golfers. The sketch below (looking across Fort Mississauga towards the residence of Charles Hunter, with Lake Ontario visible on the right, along with one of the ferries plying the route between Niagara-on-the-Lake and Toronto) shows play on the sixth green of the 1895 course.

Figure 18 Players putting in the Fort Mississauga moat on the sixth green of the Lakeside Links of the Niagara Golf Club. The summer residence of Charles Hunter is visible on the horizon in the background. Buffalo Courier, 18 August 1895, p. 9.

The full nine-hole layout of the Fort Mississauga golf course of “Lakeside Links” appears below, the first tee and ninth green shown beside the Royal Queen’s Hotel, the fourth green and fifth tee located in front of the summer residence of Charles Hunter.

Figure 19 Buffalo Courier, 18 August 1895, p. 9.

The Golf Resumés of the Contenders

Mrs. Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor – a woman born Rose Farwell (1870-1918) – was supposed to win the International Golf Tournament.

Geale’s opponent arrived at Niagara-on-the-Lake as a celebrated golfer. But she was also a social celebrity.

Figure 20 John Elliott portrait of Rose Farwell, 1889.

In 1890, she had married a Chicago man born Hobart Chatfield Taylor (1865-1945). Her husband had hyphenated his last name with an ostensibly superfluous second “Chatfield” at the insistence of his maternal uncle as a condition for inheriting this uncle’s substantial estate.

Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor had launched a career as a writer by the time he married Rose Farwell. He co-founded the political journal America in 1888, published the first of many novels in 1891 (the year after marrying Rose Farwell), lectured at universities on seventeenth-century French and Italian drama, and later wrote a highly acclaimed biography of the French writer Molière.

But Rose Farwell had gathered notoriety herself well before marrying the up-and-coming Chatfield-Taylor. Although she later won fame as a golfer, as a bookbinder (she learned the art of bookbinding in Paris), and as a suffragist, she had become famous as a teenager for her beauty.

The subject after her marriage of paintings by Adolfo Müller-Ury, she was painted before her marriage, when still a teenager, by English-born artist John Elliott. (The portrait is shown above.)

Identified universally in the newspapers of her day by her married name, Mrs. Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor was by the mid-1890s an experienced golfer of whom The Buffalo Commercial observed: “success … usually follows her on the links” (10 September 1895, p. 12).

Both her brothers and her husband were devoted exponents of the game, too, but she seems to have had a special talent, for we read that although “Mr. Chatfield-Taylor … is a fairly good golfer, he is not so good in his class as is Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor in the ladies’ events” (Buffalo Courier, 6 September 1895, p. 6).

In fact, this “young woman of great beauty and many graces … as a golfer has yet to meet a woman her superior” (Buffalo Courier, 6 September 1895, p. 6). Enthusing that “as a driver she is considered to be marvellously clean and accurate, while her putting is deliberate and clean, and her judgment of distance and gauging excellent,” the Chicago Times-Herald crowed that she “had never met any woman who could begin even to compare with her in general all-round play” (cited in Kansas City Star, 11 September 1895, p. 4).

In July of 1895, her husband had been named at the beginning of July to the organizing committee for the International Tournament, so it was widely anticipated that she would enter the competition. In due course came the announcement that she would do so, and as Saturday Night noted: “the announcement that Mrs. Hobart Chatfield-Taylor of Chicago had entered the tournament was received with the general conviction that she would assuredly add one more to her long list of victories” (14 September 1895, p. 3).

By comparison, Madeline Geale was virtually unknown to either the American or Canadian golfing public. Her entry into the tournament was unannounced, unremarked, and unheralded.

Interestingly, however, when Janet Carnochan, in her History of Niagara, wrote of the good golfers at Niagara-on-the-Lake in the 1890s, she observed that “Among the ladies, Miss Madeleine Geale was easily first” (History of Niagara [Toronto: W. Briggs, 1914], p. 260, emphasis added). Since Geale was reputed to have played daily, members of the Niagara Golf Club were no doubt familiar with her abilities. Easily the best of the women players, she would have produced scores better than many of the male members of the club. In the early 1890s, however, there were few women’s competitions between golf clubs. After all, it was only in 1891 at the Royal Montreal Golf Club that a woman (Florence Watson, née Stancliffe) was for the first time in North America admitted to membership of a golf club. So, before 1895, Geale would have had little opportunity to establish a reputation beyond the Niagara Golf Club.

But Madeline Geale’s anonymity up to the summer of 1895 would not last. All changed when the thirty-year-old golf prodigy from Niagara-on-the-Lake played a practice round with the twenty-five-year-old Chicago crack.

The Practice Round

It took just one glimpse of Madeline Geale playing a practice round with Chatfield-Taylor for the Canadian and American fans to recognize that they were in store for a very competitive contest between these two players.

The day of the practice round was sunny and hot, prompting complaints from some of the spectators, but occasional cloud cover and a strong breeze made conditions bearable.

And the strong breeze improved conditions in an unexpected way, for the practice of the women on the Fort Mississauga course was to the accompaniment of an American military band whose music was carried across the Niagara River to the links: “music … was furnished by the United States band stationed at Fort Niagara. It was a long-distance concert of an excellent sort, and the sweet strains were wafted over the river to the great delight of the golfers” (Buffalo Courier, 7 September 1895, p. 6).

Figure 21 The bottom of the photograph shows the contemporary golf course laid out around Fort Mississauga. At the top of the photograph can be seen Fort Niagara, whose military band serenaded the women playing a practice round on the Mississauga Links.

The colourful outfits of the men and women golfers drew the attention of the reporters, especially when contrasted with the cows allowed to graze on the Fort Mississauga golf course:

The golfers’ costumes were somewhat varied, the red top coats, the white trousers, and caps of the men, the white dresses, pink waists, and jaunty caps of the women, and the oddly dressed caddies, arranged in picturesque groups all over the great meadows, presenting a very pleasing landscape picture.

Early in the afternoon, a drove of over 100 cows passed over the St. George links [other newspaper reports make clear that the cows were on the Fort Mississauga links where the women’s championship was held – not the Fort George links] and one feminine golfer – properly a “golferine” – tried a long and elevating drive from the tee over the passing cows and much to her own and everybody’s surprise landed the gutta-percha ball in the midst of the cows. (Buffalo Courier, 7 September 1895, p. 6)

Whether the unknown Geale or the well-known Chatfield-Taylor played this drive into the cows is unknown, but it was well-known that they had played a practice round together, leading the Buffalo Courier to sound a prophetic note of caution to supporters of Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor:

She will play tomorrow in the ladies’ championship event and there is a possibility that her colors may at last be lowered, and that too by a Niagara girl. Miss Gale [sic] of Niagara and the Chicago beauty played a practice game that resulted in a tie, and while Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor’s prowess is not at all underestimated, it is thought that Miss Gale has an excellent show [sic] to win. (Buffalo Courier, 6 September 1895, p. 6)

Having seen the two women playing side-by-side, most reporters described the match-to-come as a toss-up. On the eve of the finals, the Buffalo Courier stated: “They are excellent players and the partisans of both are equally confident” (7 September 1895, p. 6).

After the match, the Chicago Times-Herald explained that the practice round had indeed foretold the contest to follow:

Surprise as it was [that Mrs. Chatfield -Taylor lost to Miss Geale], it can hardly be said that it was entirely unexpected.

The practice game which those two crack players had the other day, which resulted in a tie, showed that the Chicago player would have to look well to her laurels if she hoped to retain the championship and to continue her record of unbroken victories ….

The “knowing ones” who saw Miss G[e]ale play and compared her style and method with that of Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor were agreed that she would make no mean opponent and might indeed win. (cited Kansas City Star, 11 September 1895, p. 4).

Similarly, the Montreal Gazette explained in retrospect that “From the outset, it was seen that Miss Geale, of Niagara, would be the most formidable competitor Mrs. Taylor had to encounter, and as the play went on, the others gradually dropped behind, leaving these two cracks to finish together a match that for skill and closeness has yet to be equalled” (Gazette [Montreal], 9 September 1895, p. 5).

The Big Match

Accounts of the match suggest that the level of skill displayed by Geale and Chatfield-Taylor was high: “The scores of the leaders, 65 and 71, respectively, are worthy of record, significant as they are of [the] careful golf exhibited in this match, the importance of which might well influence the nerves of many players to such an extent that their play would anything but represent their actual form” (Gazette [Montreal], 9 September 1895, p. 5).

The throngs of spectators – the likes of which Madeline Geale had never seen before – were a constant reminder (if one was needed) of the importance that the golfing world was attributing to the International Golf Championship.

On Saturday, September 7th, the largest crowd of the week assembled on the Mississauga golf course, as well as on the roads alongside it, to watch the tournament’s final matches: “The concluding day of the International Golf Tournament furnished to the large gathering play of a very high order. The event that evoked the greatest interest was the ladies’ single competition in which Mrs. Hobart Chatfield-Taylor, one of Chicago’s most expert golfers, met the pick of the Canadian players” (Chicago Tribune, September 1895, p. 7).

Spectators had been just as excited in anticipation of the men’s final, “but the wind and rain on Saturday afternoon unfortunately prevented many from witnessing the finals for the championship trophy between Mr. [Andrew Whyte] Smith of Toronto and Mr. [Charles Blair] MacDonald of Chicago” (The Buffalo Commercial, 10 September 1895, p. 12).

The writer for The Buffalo Commercial describes the great crowds that came to the links daily and the sense of the occasion that animated them:

Some were only present [at the first tee and ninth green] to see the start and finish – for however much they may love golf and the golfers, not everyone cares to evidence it by following the scarlet coats over several miles of rough common, including ravines and ruined forts and innumerable other hazards so dear to the hearts of those who are skilled in the grand old Scottish game.

Many, however, braved everything and followed the players as closely as possible, the ladies silently rebelling against the rule which made anything above an inaudible whisper the gravest breach of etiquette.

At Fort Mississauga, one longed for a kodac [sic], or a camera – anything that would keep the scene from being the picture of the moment. Out beyond stretched the limitless blue lake.

Behind lay the old brown Common with a red flag fluttering here and there above the holes, while up the steep ramparts of the fort scrambled a veritable regiment of men, women and children whose one ambition was to keep as near as the rules allowed to the two red-coated players in front.

Farther on stood a line of carriages, which, with their occupants, followed wherever the course allowed. (10 September 1895, p. 12)

Figure 22 Madeline Geale, circa 1895. Charles Hunter Scrapbook. Niagara Historical Society.

Regarding the women’s final, we read that “Both played with marvellous judgement and accuracy,” but Madeline Geale seems to have played with greater consistency and control: “Miss Geale appeared to excel in driving, a feature of her play that called for the highest encomiums from the many old golfers who followed the contestants” (Gazette [Montreal], 9 September 1895, p. 5).

Chicago’s Inter Ocean newspaper said that it was her “driving and lofting” that prevailed (9 September 1895, p. 3, emphasis added).

The match was very competitive, the Chicago Chronicle observed, and it was only after “some very brilliant playing” by Geale that she was able to vanquish her Chicago opponent (Chicago Chronicle, 8 September 1895, p. 4)

Apparently, Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor often found herself facing a difficult lie.

Yet she seems to have been a bit of an escape artist (a nineteenth-century Phil Mickelson, of sorts), and so she stayed in the match till the very end: “Mrs. Taylor displayed rare ability in slipping out of awkward dilemmas, and on several occasions won out the hole when success seemed impossible” (Gazette [Montreal], 9 September 1895, p. 5). One can hear the ladies – in rebellion “against the rule which made anything above an inaudible whisper the gravest breach of etiquette” – asking themselves, “What will Rose do next?”

Figure 23 Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor. Chicago Tribune, 10 September 1895, p. 1.

Surprised that Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor had lost, Toronto’s Saturday Night magazine implied that Geale’s opponent suffered from bad luck: it seems that “Mrs. Taylor … got into one or two unfortunate hazards” (Saturday Night, 14 September 1895, p. 3, emphasis added).

Those cows!

Or was there perhaps another, more nefarious, explanation?

Partisan Canadian and American support was at a fever pitch during the championship matches, for in both the women’s and the men’s finals, an American was pitted against a Canadian.

As the eventual men’s champion, Charles Blair MacDonald, revealed many years later, a Chicago member of the crowd had bribed a forecaddie to favour him over his opponent, Andrew Whyte Smith:

Smith and I reached the finals. Smith was a very good Scotch player and, I think, quite my equal in playing the game….

A regrettable but amusing incident occurred in our match. As the golf course was quite rough, with bogs full of long grass in many places, we decided to have a fore-caddy. At one of the holes, Smith drove and almost hit the fore-caddy and then I drove. I noticed the fore-caddy going at once to where my ball lay.

Coming up, we were looking for Smith’s ball. We asked the fore-caddy where it was. He denied having any knowledge of it whatever. We told him we saw he had to dodge for fear it would hit him, but he was adamant.

Finding Smith’s ball all right, we went on.

Late in the evening, after due celebration of our victory, one of my party confessed to me that he had given the boy five dollars to be sure and always stand by my ball. (C.B. MacDonald, Scotland’s Gift, Golf: Reminiscences by Charles Blair MacDonald [New York and London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1928], Chapter 7)

Skulduggery may have been afoot on the other side, too, for MacDonald’s caddie had so greatly feared interference with MacDonald’s ball from Canadian supporters of his opponent, Smith, that he took extraordinary measures to protect it: “I shall never forget my caddy, … lying over my ball to see that no one tampered with it, as the feeling was running very high” (Scotland’s Gift, Golf, Chapter 7).

There were no reports of bribery or interference with the players’ balls in the women’s final, but one should bear in mind that the same spectators were present at the women’s final in the morning as were present at the men’s final in the afternoon.

Although they would be disappointed by the result of the men’s final in the afternoon, Canadian fans were ecstatic when the last putt dropped in the morning championship match that the Chicago Times-Herald described as “one of the greatest surprises the golfing world has been treated to” (cited in Kansas City Star, 11 September 1895, p. 4)

Big Parties

We read that during the week of the International Championship Tournament, “Mr. and Mrs. MacDonald royally entertained their many Chicago friends who… formed their house party” (Chicago Chronicle, 8 September 1895, p. 4). After MacDonald’s victory in the last match of the tournament, the Chicago Golf Club members in Niagara-on-the-Lake were as ecstatic as the Canadians had been in the morning: “Chicago won seven out of the ten prizes offered” (Inter Ocean [Chicago], 9 September 1895, p. 3).

It was time to party: “An informal party was given this evening at the MacDonald country house in Lundy’s Lane by Mr. and Mrs. MacDonald, and their Chicago and New York friends are tripping the light fantastic” (Inter Ocean, 9 September 1895, p. 3).

Rather than deferring their party until after the championship matches, as the Americans did, the Canadians partied the night before:

Mr. Charles Hunter entertained a number of the golfers at his lovely summer home, The Cedars, on Friday evening. About fifteen or twenty were present and a very jolly evening they had.

Mr. [A.W.] Smith, who so nearly escaped being Canada’s champion, Mr. J. Geale Dickson, and Capt. R.G. Dickson sang several songs, and before supper the Niagara brass band unexpectedly arrived upon the scene bent on a serenade, which they gave to the evident enjoyment of host, hostess and guests.

At the close of the evening, the golfers joined hands around the supper table and sang Auld Lang Syne. (Buffalo Commercial, 10 September 1895, p. 12)

Perhaps Smith’s party-dog performance before the championship match was a mistake. Songster Smith lost to MacDonald on the eighteenth hole.

Only Madeline Geale survived the “very jolly evening” in her best form. Perhaps she drank less than Smith, or handled the alcohol (or hangover) better.

A Farewell to Farwell

The Chicagoans were disappointed only by the defeat of Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor.

And so were American and Canadian newspapers, which worked hard to snatch some sort of victory from the fact of defeat.

Newspaper reporters found it difficult even to acknowledge that Geale’s famous opponent – “that clever golferine, Mrs. Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor of Chicago” – had really lost (Buffalo Courier, 8 September 1895, p. 11). The account of the match by the writer for The Buffalo Commercial was typical:

the ladies’ singles for the championship … ended in a final contest between Chicago [and] Canada, Miss Geale keeping the championship under the Union Jack by six strokes, making a score for the nine holes of 65 against Mrs. Taylor’s 71.

If the representative of the Chicago club lost her match, however, it was only one thing against many which she won, for she captured the hearts and unbounded admiration of everyonewho saw her.

She is exceedingly handsome, with a fascinatingly bright smile, and a sweetly unconscious smile, which is only one of her many charms. (10 September 1895, p. 12, emphasis added)

“If” she lost her match?

Chicago’s Inter Ocean newspaper mixed compliments with excuses. On the one hand,

Mrs. Chatfield Taylor did some splendid work…. There were eight entries in the ladies’ contest, and Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor was the only American in the match. She has been in form but three months and, considering the field against her, she made a magnificent showing. The Canadians were profuse in their praise of her pluck and brilliant playing. (Inter Ocean, 9 September 1895, p. 3).

On the other hand, Geale’s knowledge of “every nook and corner of the links” was “an advantage which the Chicago lady could not overcome” (Inter Ocean, 9 September 1895, p. 3).

The Chicago Times-Herald suggested that the Chicago champion might have prevailed but for the cows:

On several occasions, the ball would land in a muddy hole or cow path, and it was almost impossible to loft it.

For these reasons, a stranger to the links, not knowing where or how to avoid these places, was greatly handicapped, and this, in no small degree, as well as Miss Gale’s knowledge of the course, conspired to defeat Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor. (cited in Kansas City Star, 11 September 1895, p. 4)

Events “conspired” against the Chicago lady.

The Canadian press was equally sympathetic – if not more sycophantic – in explaining (away) Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor’s loss.

We read in a number of Canadian newspapers that “Although Miss Geale won, it cannot be taken for granted that Mrs. Taylor is an inferior player” (Gazette [Montreal], 9 September 1895, p. 5).

Saturday Night implicitly offered the second-place finisher an honorary “Mrs. Congeniality” award:

Mrs. Taylor and Miss Geale … played so evenly that up to the last it was either’s match. Mrs. Taylor, however, got into one or two unfortunate hazards and lost by six strokes, the score being sixty-five and seventy-one for the nine holes.

Mrs. Taylor played a very pretty game, but far prettier than the game was the player.

She is exceedingly handsome, tall and graceful, with a charming face, pretty light-brown hair and a warm, soft, nutbrown complexion. And her manner is as frank and charming as her face.

During her short stay at the Queen’s, she made many friends and admirers. (Saturday Night [Toronto], 14 September 1895, p. 3).

To paraphrase Alexander Pope’s observation about reaction to flaws in the fair maid Belinda in The Rape of the Lock:

If to her share some golfing errors fall,

Look on her face, and you’ll forget ’em all.

And so, despite her loss to Geale, Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor was even more celebrated when she left Niagara-on-the-Lake than when she arrived: she had conquered hearts.

But Madeline Geale had broken the aura of invincibility that accompanied Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor on the golf course.

And she may have undermined her confidence, too.

Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor returned to Chicago immediately after her Niagara-on-the-Lake loss, eager “to enter the play again” in a tournament the next day (Chicago Chronicle, 10 September 1895, p. 4). It was said that she had returned to Chicago “looking none the worse for her defeat in Canada, where she was a good second,” but “strange to say, she had to put up with her second place, her conqueror on this occasion being Miss Carpenter, a young woman only 14 years old” (Chicago Chronicle, 10 September 1895, p. 4).

Despite these first two losses of her golfing career, suffered in the consecutive tournaments she played in September of 1895, Chatfield-Taylor continued to play golf at a high level in the Chicago area for many more years.

In 1918, however, at just forty-eight years of age, she died of pneumonia at the family’s home in Santa Barbara, California, after what had seemed initially to have been a successful operation to remove her appendix.

Golf Pretty

Figure 24 Rose (Farwell) Chatfield-Taylor, c. 1895.

Travelling back to Chicago on the overnight train after the finals in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Chatfield-Taylor arrived at her home golf course the next day ready to play another tournament.

As noted above, she was described as “looking none the worse for her defeat in Canada” (Chicago Chronicle, 10 September 1895, p. 4).

All was well, both with her golf game and with her looks: “Mrs. Taylor [had] played a very pretty game, but far prettier than the game was the player.” (Saturday Night [Toronto], 14 September 1895, p. 3).

And so, after the gruelling final match of the International Championship Tournament, the one was ‘looking none the worse for her defeat.”

What about the other one? Was Madeline Geale looking any the better for her victory?

Figure 25 Madeline Geale, circa 1895.

Belatedly, the Canadian woman who was the first to defeat the pretty Chicago woman was also described by a newspaper as pretty – in fact, as exceedingly so.

In her History of Niagara, Janet Carnochan recalls that “in the [Toronto] Mail and Empire of 1896, where her picture appeared, she was described as having the prettiest golf stroke among women players of the time” (p. 260).

A second victory: Miss Geale’s golf swing was prettier than Mrs. Chatfield-Taylor’s!

Ah, but how did the pictures compare?

Hattie Gale

Several American newspapers referred to Mrs. Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor’s opponent as Hattie Gale.

Madeline Geale’s name first appeared as such in the Buffalo Courier: “Much interest centers in the ladies’ match. The competitors will include Mrs. Hobart Chatfield-Taylor of Chicago and Miss Hattie Gale of Niagara-on-the-Lake. They are excellent players and the partisans of both are equally confident” (7 September 1895, p. 6).

I suspect that the American reporter who produced the above “Special” report from Niagara-on-the-Lake had heard Madeline Geale referred to familiarly as “Maddie,” but misheard this name as “Hattie.” Or perhaps he had submitted a handwritten story to typesetters with the name “Maddie” in it, but typesetters misread “M” and “d” as “H” and “t.” Or the reporter may have submitted the story by telephone, his “Maddie” being misheard as “Hattie.” This would also explain how “Geale” (pronounced “gale”) came to be printed as “Gale.”

The problem was perhaps a “game of telephone.”

Whatever the case may be, Hattie Gale became well-known in Chicago.

The Chicago Chronicle reported that “the ladies’ championship …. narrowed down to a contest between Mrs. Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor of Chicago and Miss Hattie Gale of Niagara-on-the-Lakes” (8 September 1895, p. 4, emphasis added).

Similarly, Chicago’s Inter Ocean newspaper reported that “Mrs. Hobart C. Chatfield-Taylor played a plucky game with Miss Hattie Gale, Canada’s champion lady golf player of Niagara-on-the-Lake” (9 September 1895, p. 3).

And the Chicago Times-Herald referred sensationally to “one of the greatest surprises the golf world has been treated to. This was none other than the defeat, after a notable struggle, … of Mrs. Hobart Chatfield-Taylor of Chicago by Mis Hattie Gale of Niagara-on-the-Lake” (cited in Kansas City Star, 11 September 1895, p. 4)

At least Hattie Gale was from Niagara-on-the-Lake (or Niagara-on-the-Lakes). In many reports carried in newspapers across the United States, however, Madeline Geale was reported to be just another of Chicago’s top golfers:

Chicago Women Play Golf

Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., Sept. 9 – The international golf tournament closed with the ladies’ single competition. There were several competitors in this event, which finally simmered down to a contest between Mr. Hobart Chatfield-Taylor, of Chicago, and Miss Geale, of Chicago. The struggle between these two was notable one, Miss Geale finally winning by a score of 65 to 71. (Champaign Daily Gazette [Illinois], 9 September 1895, p. 2)

Although in Buffalo they knew that the International Championship Trophy had been kept “under the Union Jack,” people in most of the other states were told that it resided under the Stars and Stripes (Buffalo Commercial, 10 September 1895, p. 12)

Laureate Golf Career

As a result of her big win in the first International Golf Championship, Madeline Geale became wellknown in small world of North American golf in the mid-1890s. From this point of view, note that the photograph that she gave to her admirer and mentor Charles Hunter contains her autograph.

Figure 26 Autograph of Madeline Geale, circa 1895.

One wonders if the two photographs above that show her holding golf clubs were taken precisely for the purpose of distributing autographed copies of them as occasion required (whether to individuals or to newspapers such as Toronto’s Mail and Empire).

Geale was almost single-handily responsible for the taking up of the game by the first generation of women golfers in Buffalo: “Tennis and bowling on the green continue to be popular, but golf has the call with the fair sex. Many Buffalo ladies are becoming enthusiastic golfers and have the advantage of the coaching of Miss Madeline Geale, the secretary of the Niagara Golf Club, who is probably the cleverest woman golfer in America” (Buffalo News, 6 July 1896, p. 40). Geale had at least eight Buffalo pupils at the beginning of the summer, and probably had a good number more as the summer passed and word of her success as instructor spread.

In the spring of 1896, the Niagara Golf club proudly claimed that Geale was “probably the best woman player on this side of the Atlantic” (The Globe [Toronto], 19 June 1896, p. 10). And, as we have seen, the Buffalo News described her that summer as “probably the cleverest woman golfer in America” (6 July 1896, p. 40).

And so golf fans were very interested to see a rematch between Geale and Chatfield-Taylor, the Toronto Golf Club proposing to insert its own champion into such a contest: “A ladies’ golf match is also on the lapis [that is, “on the schedule”], and Mrs. Chatfield Taylor of Chicago has been invited to play on the Toronto links … Miss Geale of the Niagara Golf Club, and Miss Ethel White of the Toronto Golf Club, for a trophy which has been offered by the Niagara Club” (Saturday Night [Toronto], 12 September 1896], p. 2).

I find no evidence that such a match ever occurred, but in the spring of 1897, Madeline Geale and Ethel White engaged in a match-play contest on the Toronto links (White’s home course): it ended in a draw (The Globe ] Toronto], 18 May 1897, p. 10).

And within a year Geale had become a member of the executive committee of the Niagara Golf Club: “This is probably the first time in America that a lady has been elected Secretary-Treasurer of a golf club, but Miss Geale … is a lady of great executive ability and business capacity and has always taken the greatest interest in golf at Niagara” (The Globe [Toronto], 19 June 1896, p. 10).

She was thereby in charge of the budget for laying out the new eighteen-hole golf course on the Fort George Common:

This year, at the annual meeting held on the 13th [June], several hundred dollars were voted towards having the course put in the best possible order – a resolution which the executive committee lost no time in setting in motion. The Fort Mississauga links have been given up and a very beautiful eighteen-hole course completed on the Fort George commons. (Buffalo Commercial, 20 June 1896, p. 13).